The Printing Press Is Putting Honest Monks Out of Work

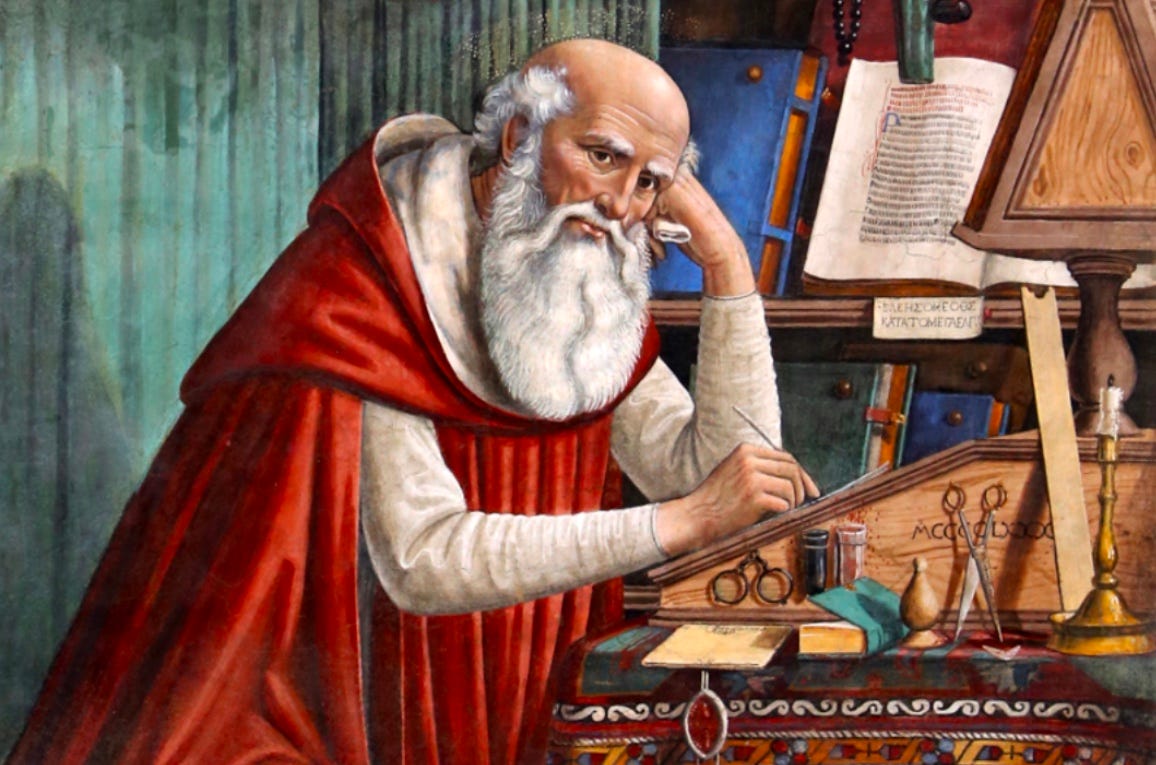

Words were meant to be written by a scribe’s hand

By Johannes the Bookish

For centuries, learnéd monks such as I have toiled away in monasteries painstakingly copying books by hand. By the sweat of our brows we have laboured to bring knowledge to those few wealthy souls who could afford the extravagant pryce of a single book.

But now, technology threatens our very livelihood and all we have worked so hard to build. This new invention called the “printing press” is putting honest monks out of work, and it must be stopped.

What is at risk here is not just our jobs, but our very souls. If we start printing Bibles, what then shall become of all the hardworking monks in the Kingdom’s monasteries? Are we to get “jobs” or do “productive work” like some kind of lowborne swine? Are we to sully our robes in the mud “preaching” the “word of God” from our “mouths” to pestilent knaves on the street? Will the profits from book sales go to lay publishers instead of into the Church’s coffers?

I say this printing press is the invention of Satan himself, or possibly even womyn!

What’s worse is the speed and low cost of printing risk putting knowledge in the hands of mere peasants. Peasants! Only God knows what calamities might befall us if peasants are allowed to know things.

Nay, I say! Knowing things is the realm of nobles and men of the cloth. Toiling obediently is the realm of peasants. If the peasants no longer rely on us, their betters, as their only source of information, it could throw our precious Social Order into Chaos.

‘Tis a slippery slope, methinks. ‘Tis only a matter of tyme before the printing press is used to print smut, like books about “science” or pictures of ankles. The minds of the masses shall be driven mad by these etchings till they can think of naught but bared tarsals and heliocentric models of the cosmos.

Luckily there’s some things a machine can ne’er replace. It can ne’er replace the feel of a wet quill upon vellum. It can ne’er replace a true scribe’s ability to draw original marginalia, like jousting rabbits or a dæmon shooting an arrow into a merman’s rectum, which I assure thee both have religious significance. It can ne’er replace the élites’ ability to control the flow of information by limiting distribution of books to the upper classes and the clergy.

Such things are the realm of scribes, not presses. So support thy local monk; refuse to buy printed books.

Addendum: In Praise of Scribes

He who gives up copying because of the invention of printing is no genuine friend of holy Scripture… Printed books will never be the equivalent of handwritten codices, especially since printed books are often deficient in spelling and appearance.

-Johannes Trithemius, In Praise of Scribes

Socrates, in Plato’s Phaedrus, lamented that the oral storytelling tradition of the Greeks — and along with it the ability to remember things — was being replaced by the written word. The monk Johannes Trithemius, writing not long after the invention of the printing press, worried that printing would eliminate the many benefits of copying books by hand. More recently, people complained that the Web was killing print publishing. Certainly at some future point, we’ll complain that whatever comes next is killing the Web.

Right now the debate seems to be whether artificial intelligence-generated art and writing will replace creative work done by humans.

An A.I.-Generated Picture Won an Art Prize. Artists Aren’t Happy.

you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth1

The College Essay Is Dead - Nobody Is Prepared for How AI Will Transform Academia

they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing… they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without reality.

Robots Trained on AI Exhibited Racist and Sexist Behavior

they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing

With any new technology there is a tradeoff. Some benefit of the previous way of doing things will be lost, while some new benefit will be gained. This has been the case with each of the transitions from oral, to the written word, to print, and finally to the internet. Presumably each of these methods of communicating was widely adopted because it was better in some way than the previous method.

It remains to be seen what kind of staying power AI-generated art will have. There’s something called the Lindy effect, where the longer an idea or technology has been around, the longer it is likely to continue to be around. By this measure, AI is on shaky ground. Will it be the next printing press? Or will it go the way of the Palm Pilot after its brief moment in the sun?

Before diving more into AI, let’s look briefly at some previous technological transitions to see if these can help inform our predictions about AI-generated content.

From Oral Tradition to the Written Word

Socrates worried that writing would destroy people’s ability to remember things and thus attain true wisdom. What reason is there to remember if you can just look it up later in a scroll? So one thing lost was our collective ability to remember things.

Oral storytelling is, by its nature, a social event. There’s a performative and interactive element about it that is lost when put in writing. Book readings and book clubs aside, reading books is more of a solitary endeavor, so the social aspect of the oral tradition was mostly lost with the move to writing.

The benefit the written word has over oral storytelling is that it can last much longer and reach much farther. The reach of a written story is not limited to the audience standing in front of the teller. Were it not for the written word, we would know much less about the ancient world than we do. In this regard, I think the creation of writing was worth it.

From the Written Word to the Printed Word

Trithemius’s main gripes about printing were that it would make monks lazy, and that printed books don’t last as long as handwritten words on parchment. He was right that there is benefit to painstakingly copying a book by hand. Being actively involved in the process of a copying each letter would have helped a scribe fully absorb the text more so than simply reading it. The uniqueness of the marginalia in each handwritten book also gives character to old texts that doesn’t quite exist in print.

And they do last longer. The St. Cuthbert Gospel is about 1,300 years old and still looks pretty great. Books in my house rarely last a week before my kids destroy them with orange juice and hate.

The downside of hand copying was that there was a limit to how many books could be produced, and they were expensive. Printing allowed knowledge to spread to a much greater part of the population. Because it was cheap, it also allowed many new types of writing to be produced. While each individual printed book may be inferior to a handwritten one, in the aggregate printing greatly increased overall access to information.

From the Printed Word to the Online Word

Then came the Web.

It took the spread of knowledge started by the printing press and kicked it into overdrive. Today an estimated 63.1% of the global population has internet access. That’s almost two-thirds of the world with the entire history of human knowledge available at the click of a button. The potential for educating people and connecting people and ideas is greater than at any point in history.

The downside is information overload. It’s easy for us to get a million tiny bits of information thrown at us from all angles and yet never absorb anything of substance. Learning takes time and focus, and the last thing the internet wants you to do is focus.

But I think this is mainly a flaw in the way we use the internet, rather than a flaw with the internet itself. It is possible to focus and use the internet to learn things. You don’t have to get distracted by notifications and social media updates if you choose not to. There’s a lot more bad content online than there is in print, but there’s also a lot more content in general. Maybe the good stuff online is a little harder to find than the good stuff in print, but there’s plenty of good stuff out there. Because of its accessibility and massive reach, I think the Web has enough pros that it’s worth keeping around.

Trading Quality for Quantity

If there’s one trend across all of the above developments, it’s that with each new technology, some degree of quality was sacrificed for quantity.

Writing replaced the performative, social, and memory aspects of oral storytelling, but it allowed the ideas to be spread farther and have more permanence.

Printing created cheaper and slightly-lower-quality versions of handwritten books, but distributed them to the masses.

The Web added heaps of low-grade garbage on top of the existing corpus and destroyed our collective attention spans, but it allowed gigantic amounts of information to be accessible to everyone in an instant.

The famous Library of Alexandria had between 200,000 and 700,000 books (mostly in the form of papyrus rolls). Today somewhere between a few hundred thousand and a few million new books are published each year. That’s more than the entire Library of Alexandria, per year. On top of that a couple million articles are published every day. While that quantity puts the greatest library of the ancient world to shame, I imagine the ratio of quality books in the Library of Alexandria was much higher than in the millions of books and articles that were published in 2022.

With this greater quantity/lower quality transition, art is more likely to lose its staying power. According to the Lindy effect, the expected lifespan of the internet is much shorter than that of print, and oral storytelling has the longest expected lifespan of all. And we can see this in everyday life. Internet articles are ephemeral, but books, especially the good ones, are around for a long time. The Iliad has been around for 3,000 years or so. It will continue to be around a lot longer than this article, even though this article was published using the latest and greatest technology, and the Iliad was originally told by word of mouth.

Draw Me Like One of Your AI Girls

Which brings us to AI-generated art and writing.

A big potential benefit is that it can make it much faster and easier to generate content. I’ve occasionally used AI-generated images in this newsletter. Things that previously would have taken me 5+ hours to draw I can now generate in 15 minutes with a few text prompts and some experimentation. For this massive one-man content mill that is Ye Olde Tyme News, it makes it much easier for me to quickly get images so I can focus on the writing. It’s also good for brainstorming and idea creation. Just type a prompt and see what kind of crazy stuff it can come up with to help spark new ideas.

One downside of AI, at least for the time being, is that it kind of sucks at its job. This is what the Midjourney bot gives me when I tell it to draw a “camel standing in the desert with a hat on”:

A bigger downside, as with the transition from hand-copying to print, is that something is lost in the act of creation. Spending 5 hours to draw a feature image that you, the reader, would only look at for .5 seconds was a pain in the ass. But I enjoy drawing, and I learn something every time I draw.

I still draw comics, and I draw images for the articles when I have the time, but like Trithemius’s monks I sometimes take the lazy way out with AI art. For my purposes, where the focus is the writing, AI art has been a positive thing. Some things, like a dead nobleman buried in amulets or a Recon Faerie, are a little beyond my skillset to draw well, and there are no public domain images available for free online for those types of things. So AI art has really helped me there.

It would be great if I was a talented artist with many free hours each day to spend drawing, or if I had endless streams of cash with which to pay other artists to draw for me, but that’s just not the case.

If AI-generated content ends up sticking around, and if the past is any indication, it will likely compound the quality vs. quantity tradeoff that has been going on for the last few thousand years. There will be way more stuff, but also way more shitty stuff. There will be some more good stuff, too.

More people will be able to create things. Most of it will be crap, but some of it will be good.

Probably the biggest and most controversial problem posed by AI art is whether it will take creatives’ jobs. The outlook here is not all rainbows and AI-generated unicorns. It will be cheaper than ever to create certain types of art and writing, so for some artists and writers, especially those at the bottom, those jobs will pay less than ever. In Socrates’ day people asked, “Why would I bother remembering something when I could read it later in a scroll?” Tomorrow they’ll ask, “Why would I bother paying someone to write a forgettable article about Beyoncé’s new sofa when I can click a button and have the computer write it for free?”

Many writers’ and artists’ jobs will be at risk. If I was a copywriter or someone who made art for advertising or something intended to be mass produced I would be pretty worried. At the same time, I think it will create new and different types of creative jobs. AI can’t stop people from being creative. Humanity has an innate drive to create, and we will continue to do so, AI or no AI.

Right now, a pitching machine can throw harder than a human, but we still restrict baseball teams to only having humans on them. An automated motorbike can cover 100 meters faster than any human, but we don't allow motorbikes to compete in an Olympic sprint competition. A mechanical sumo wrestler wouldn't need to be intelligent, just heavier than the heaviest competitor, and it could already win against any human right now, but we don't do that.

-nonameiguess, from this thread on Hacker News

With each transition above, some types of jobs were lost, but others emerged. Typically these changes created more opportunities for creators, rather than fewer. Before the internet it was difficult for the vast majority of the population to have their ideas seen and read by others. Before the printing press, it was nearly impossible.

I would guess that more people are employed in “creative” work today than at any point in history, although the nature of the work is constantly evolving. Like scribes in the early days of the printing press, people will have to adapt. There’s few jobs today where a wealthy nobleman will pay you to sculpt him with rippling muscles and a small…ego, or where the Church will employ you for four years to paint the ceiling of a chapel. Nobody expects that. But expectations about being paid $100+ as a freelancer to write a listicle or to draw the cover art for a self-published erotic e-novel might have to change.

No matter how good AI gets, there will still be art created by humans. The existence of AI doesn’t make the work of humans any less beautiful or moving or original.

But many creatives will have to find new and, dare I say, creative ways to make money. Alas, I’ve been writing and drawing comics for 7 years and still don’t make money from it, so the person to figure out how probably won’t be me. But I’m hopeful that someone will. And I’m hopeful that good art and writing will continue to be created by humans.

After all, none of the new technologies above completely replaced the previous ones. I can still sit around a campfire telling stories. I can still buy 1,000 pieces of parchment on Amazon and sit in my basement copying the Bible by hand if I so choose. I can still draw a picture on paper. I can still read a book.

And I will continue to do these things. At least until our AI overlords take over the world and harvest my organs for energy.