How Affordable Was Life in the Middle Ages?

Or, it pays to be a peasant

Compared to our lives today, life in the Middle Ages was much simpler. If you were a peasant you worked the land by day, got drunk in the local tavern by night, and occasionally got called off to a war whenever the lord was feeling ambitious. If you were a lord or lady you hosted feasts, went sauntering through the forests atop your steed, and occasionally levied your vassals into the militia whenever you were feeling ambitious. The many travails of modern life, like paying bills, paying taxes, making rent, and getting a job didn’t exist.

Ah, how quaint was life!

Or was it?

As different as life in the Middle Ages was from life today, people then were faced with many of the same challenges. They still needed to eat. They still needed a roof over their heads. They still got married and had children and attended the local beheading with their friends. All of these things cost money (beheading aside, unless you wanted to buy some ale and turnips to throw at the condemned).

As there is much modern discourse about inflation and the rising cost of living, I thought it would be interesting to look at the cost of living in the Middle Ages to see if and how things have changed since then. Luckily, at least one online source has compiled data on wages and costs of various items in the Middle Ages. Most of the medieval data below come from Kenneth Hodges1, who compiled them here. Most of the US data comes from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), unless otherwise noted.

This article will compare the costs of various living essentials relative to income during the Middle Ages to the costs of those same things in the modern United States. Hopefully we’ll gain some insights into which period of history was more affordable.

Or maybe we won’t. But it will still be fun.

The average American household2, according to BLS, made $87,432 before taxes in 2021. Their largest expenditures were, in this order:

Housing ($22,624)

Transportation ($10,961)

Food ($8,289)

Personal insurance and pensions ($7,873)

Healthcare ($5,452)

Entertainment ($3,568)

Cash contributions (e.g., charitable donations, $2,415)

Apparel and services ($1,754)

Education ($1,226)

Alcohol ($554)

So we’ll look at most of these (I’ve excluded a few categories if there was no solid medieval data or if they just weren’t that interesting). Of course, we’ll also look at another huge expense: taxes. The data on taxes is a little bit more complicated, especially for the Middle Ages, but we’ll give it a shot.

Before We Get Started

There’s few assumptions and caveats to be aware of.

For starters, this data is primarily from late medieval England, and doesn’t necessarily represent affordability in other parts of Europe or during different time periods.

Secondly, the numbers below assume that inflation during the Middle Ages was essentially zero. The dates they’re taken from generally range from the 13th to 15th centuries. While prices for certain items could swing dramatically from year to year, overall inflation during the Middle Ages was pretty much zero. Big time inflation didn’t really kick in until the “price revolution” of the 16th century, so I think this is a safe assumption to make for our purposes.

Thirdly, I have converted all medieval prices to pence for simplicity. The prices and wages I could find are given in various different formats and coinages (e.g., wages are variously given in daily and annual rates; monthly rent is listed for some types of dwellings, but for other types of dwellings the only price listed is the cost to build the dwelling; prices are variously listed in pounds, shillings, pennies, marks, groats, etc.). I did my best to try and make sense of them. Conversion rates are in the footnotes.3

Lastly, a lot of the data from the Middle Ages can be vague and incomplete, at best. I am neither a historian nor a statistician, so this is merely a layman’s analysis and visualization of the data that exists.

Thusly, let us begin with perhaps the biggest expense, both then and now: housing.

Housing

As a percentage of annual income, housing costs for skilled tradesmen in the Middle Ages who were renting their dwelling likely ranged from much lower to slightly higher than those of the average American in 2021.

At 12.5% of annual income, rent for an unskilled laborer was about half of what it is for a modern American household.

Some more details on these numbers:

An early 14th century Laborer made at most 480 pence/year. I’m assuming a laborer lived in a cottage, the cheapest type of dwelling, which rented for 60 pence/year. The percentage here is for a Laborer making the maximum of 480 pence/year.

A Master Carpenter made 3 pence/day and a Master Mason made 4. I’m assuming they worked about 240 days/year (more on that in “Do You Work More than a Medieval Peasant?”). So that’s 720 and 960 pence/year, respectively. Rent for a craftsman’s house was 240 pence/year and is reflected in the “high estimate.” Rent for a cottage was 60 pence a year and is reflected in the low estimate. As skilled craftsmen, I assume masons and carpenters would have lived in craftsmen’s houses, and that the high estimate is more accurate, but I wasn’t sure so included both. Carpenters/masons would have done most of their work on a construction site, so maybe they wouldn’t need to splurge on a craftsman’s house. It’s also possible that many of them worked more or less than 240 days.

The Average American household spent $22,624 on housing in 2021, just under 26% of annual income. This housing cost includes both homeowners and renters, because the way BLS broke it down between homeowners and renters honestly doesn’t make sense to me.

I didn’t include other medieval professions, such as merchants, soldiers, and nobility, because their incomes and types of living quarters varied widely. But rent for a merchant’s house in the early 14th century was 480 pence/year, plus an extra 720 pence/year for labor (I’m assuming that means servants and general upkeep). Wages for the military ranged from Welsh infantry on the low end at 2 pence/day, to a mercenary knight banneret on the high end at 48 pence/day. (The Welsh were always getting screwed!)

The numbers are a little more varied when we look at the costs of buying or building a house.

For unskilled laborers, it looks like building a cottage was much more affordable than buying or building a house in 2021.

For skilled laborers, it really depends what type of house they were living in. A “Cottage” would have been far more affordable than a house in the modern US, but a “Craftsman’s House” would have been less affordable. Hodges also lists the price to build or buy a “Row House in York,” which is 2.5 times the cost of a cottage but much less expensive than a Craftsman’s House.

For the Low-level Baron, “House with Courtyard” was the most expensive non-castle dwelling on Hodges’s list, so I assumed this would be more similar to a “poor” baron’s living situation than a castle, which would be outrageously expensive.

More on these numbers:

The median sales price for a home in the US in the fourth quarter of 2021 was $423,600, and that’s the price used here.

The cost to build a “Cottage (1 bay, 2 storeys)” was 480 shillings, the same as the highest possible income for a Laborer. This price is used for the Laborer, as well as the low estimates for the Carpenter and Mason.

The cost to build a “Craftsman's house (i.e., with shop, work area, and room for workers) with 2-3 bays and tile roof” was 6,000 pence - 2,400 pence for materials, 3,600 for labor.

The cost to build a “House with Courtyard,” which was used for the Low-Level Baron, was 21,600 pence. A baron’s annual income ranged from 48,000 - 120,000+ pence. I used the lowest number, assuming a wealthier baron would have lived in something nicer than “House with Courtyard,” as nice as that sounds.

The cost to build a castle was exorbitant, and probably varied widely based on the castle. So I did not include it here. Some numbers for castle building that Hodges gives are (note that the first two are just parts of a castle and not the whole thing):

Stone Gatehouse (40' X 18'), with stone: 7,200 pence

Tower in castle’s curtain wall: 174,720 pence (Materials - 79,920 pence; Labor - 94,800 pence)

Castle and college at Tattershall: 108,000 pence per year for 13 years; 1,296,000 pence total. It would have taken a 14th century laborer 2,700 years of wages to afford one. I don’t think there’s any reasonable way to compare this to the cost of a modern house, but the mean American construction laborer in 2021 made $44,130. In my totally non-scientific calculations that would be something like a $119 million house today.

Conclusion: Housing was probably more affordable for most people in the Middle Ages than it is in the modern US.

Transportation

The second biggest cost for modern Americans is transportation. This includes vehicle purchases/payments, fuel, and public transportation.

This is one that’s hard to compare to the Middle Ages, since most people didn’t really have to travel anywhere. A peasant very possibly could have lived his entire life within walking distance of his house.

If somebody did decide to buy a form of transportation, it looks like it was very unaffordable unless you were among wealthiest people in the Middle Ages. Probably there were other less expensive options that weren’t listed on Hodges’s list. Donkeys and mules would have been less expensive than horses, and a regular person probably could have built a cheap cart themself rather than buying an iron-bound cart.

Overall, I don’t think these numbers tell us much, since the nature of and need for transportation was so much different. The cost to a knight of buying and maintaining a horse was exorbitant, although a single knight’s horse was roughly equivalent to the average American’s expenditures on transportation. It’s also important to consider that most Americans don’t use their cars to go to war. A warhorse is probably more equivalent to an American buying and maintaining an up-armored Humvee than a minivan.

An iron-bound cart cost 48 pence. An ox cost 157.25 pence.

A mercenary knight made 24 pence per day in the early 14th Century. Assuming he was employed during a war and was paid every day, that’s 8,760 pence in a year. The cost for “Knight’s 2 Horses” was 2,400 pence. Hodges also lists a price for “High-grade riding horse,” which is also 2,400 pence.

Income for Earls varied dramatically, from 96,000 pence/year to well over 2.5 million pence. The cost of a Warhorse in the 13th Century was 19,200 pence. Upkeep for 82 days in the summer months was 441.5 pence.

The average American household spent $10,961 on transportation in 2021. That is a massive expense, and it makes me want to take a cue from our peasant brethren and live my entire life within walking distance of my house.

Conclusion: The nature of transportation was dramatically different in the Middle Ages than it is today, so it’s not all that helpful to compare the two. Horses and cars were and are expensive as shit.

Food

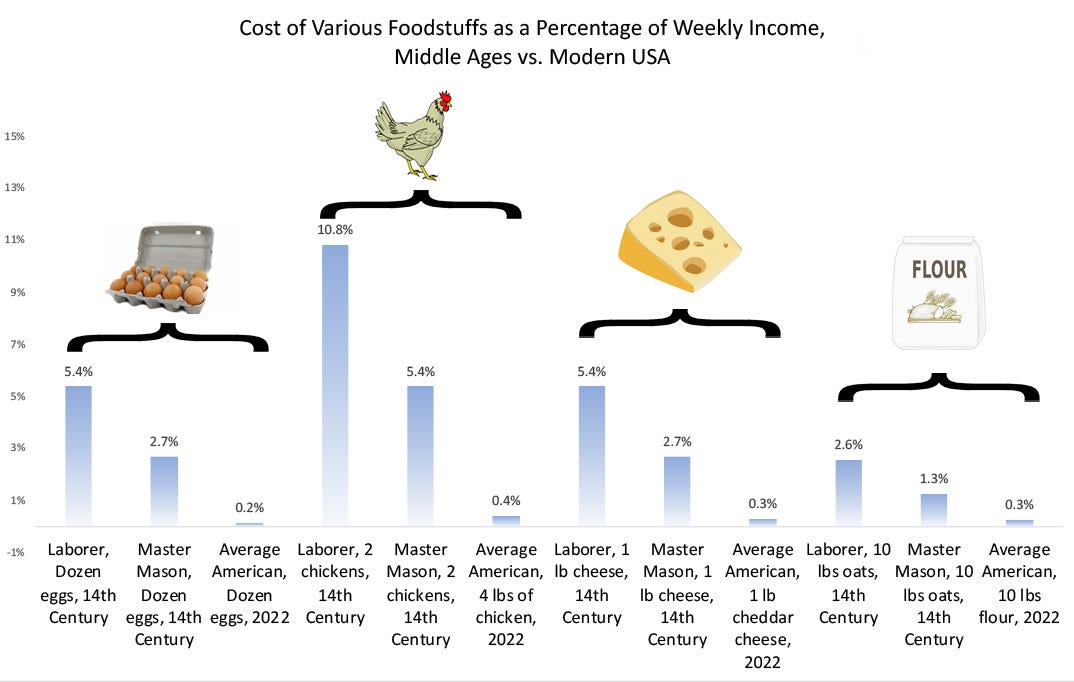

The chart below compares the cost of specific foodstuffs for a 14th century laborer, 14th century Master Mason, and an average American household in 2022.

Looks like medieval laborers probably weren’t eating much chicken.

Food items were much less affordable in the Middle Ages than they are in the modern US. That said, many medieval households grew their own food and had animals, animals which reproduced. They might have bought a few chickens and a rooster, then those chickens could lay eggs and turn into more chickens over time. So the 14th century person probably didn’t have to buy food with nearly the same frequency or in the same amounts as we do today. They would still need to feed and care for the animals, but that would have been much less expensive than buying fresh chickens every week.

Some more details on the numbers:

Eggs: The cost of eggs in the U.S. rose dramatically in Oct-Dec 2022. The price I used is the average for the year, $2.86.

Chickens: The Middle Ages prices are per 2 chickens. The BLS data is by the pound. Google tells me the average rotisserie chicken weighs about 2 pounds, so I figured 4 pounds of chicken was about the equivalent of 2 chickens.

Cheese. Yum.

Oats/flour. The Middle Ages data lists prices per quarter ton of oats. BLS data doesn’t list prices for oats, but does have prices per pound of flour, which is similar enough. I converted each to the cost per 10 lbs because that fit the most nicely on the chart.

Conclusion: Food was much less affordable in the Middle Ages, but people probably produced more of their own food and didn’t have to buy as much.

Entertainment

What exactly did medieval people do for fun? Surprisingly, quite a lot.

For the nobility, hunting, falconry, and tennis were favorite pastimes. Peasants might have enjoyed singing, dancing, telling stories, going to plays, and getting drunk at festivals. In many ways they were smarter than us when it came to entertainment: The things they did were more wholesome, and for the most part they were free.

But free doesn’t look good on a chart. So here are price comparisons for various entertainment-like items, given as a percentage of monthly income.

Okay, so maybe most people wouldn’t consider a funeral to be “entertainment,” but there were good numbers for comparison.

Books get their own chart based on annual income, because they were so outrageously expensive before the invention of the printing press.

Some more on the numbers:

Tickets: I’m still using the income for a 14th century laborer/mason, but didn’t have data on ticket prices from the 14th century. So I used data from The Globe, which says around the year 1600 the cheapest tickets cost 1 penny.

The cheapest Taylor Swift tickets are going for about $360 right now on StubHub. The average movie ticket in 2021 cost $9.57.

Books: 126 books cost 27,120 pence in the 14th century, or about 215 pence per book. 2 books cost almost as much as a small house! A laborer, master mason, or other regular person most likely would not have owned any books, because they couldn’t afford them and probably couldn’t read. Modern books generally range between $13-20, which is pretty negligible compared to annual income.

I wanted to compare wedding costs, but they vary too greatly. A “wealthy peasant’s wedding” cost 720-960 pence in the 14th century, much more than an ordinary laborer or craftsman could afford. The average US wedding cost $28,000 in 2021, according to The Knot. That’s 32% of the average household’s annual income, more than is spent annually on rent.

Try not to die anytime soon, because that’s also expensive.

The average American spends about 4% of their income on entertainment, not including entertainment-adjacent things like weddings and dining out. This is one area of modern life where living like a medieval peasant could lead to real cost savings for all of us. What if, instead of going to concerts and movies, subscribing to dozens of streaming services, and buying all the latest tech gear, we instead chose to sing, dance, and tell each other stories?

I’ll tell you what if: You could save $3,568 a year.

Conclusion: Entertainment was less expensive in the Middle Ages, largely because of the nature of the things people did for fun. Caveat: Books were much more expensive.

Apparel and Services

Individual clothing items are more affordable across the board in the modern US. That said, people today have way more clothes than a normal medieval person would have.

To find out how much clothes a medieval person would have owned, I turned to the scholarly world’s primary source of accurate information: Reddit. This thread from r/AskHistorians has some great information on clothing in the Middle Ages. The bottom line is that most poor people would have owned only one set of clothing. Clothing could also be given as charity, from the rich to the poor:

In addition to the healthy market in secondhand clothing (really, medieval thrift shopping!), rich people often used 'free' donations of clothing as an incentive for poor people to attend their funerals (that is, to get more prayers for their soul, in theory).

-u/sunagainstgold

Highly recommended if you have extra clothes lying around when you die, and you really want to lock in a spot in Heaven.

The average American spends 2% of their annual income on apparel and services. A medieval laborer would need to wear the same tunic and pair of shoes for a little over two years to spend an equivalent amount of their income on apparel.

Conclusion: Individual clothing items cost more in the Middle Ages than they do today, but people owned far less clothing.

Education

Now to my second favorite chart in this story.

It’s important to note that universities in the Middle Ages were limited pretty much exclusively to wealthy, upper-class males. Based on the numbers, there was no way a regular person could afford a college education. The lowest level person that ostensibly could have afforded one was an esquire, which is a level below a knight. Maybe a rich or well-connected peasant got in from time to time, but this probably wasn’t the norm.

While college is still expensive today, it’s accessible to a much larger part of the population. In this regard, things have improved dramatically.

Oxford claims there is “evidence of teaching” occurring there as early as 1096, which would make it the second oldest university in Europe, after the University of Bologna (1088, also a disputed claim). Women weren’t admitted as full members until 1920.4

Conclusion: The cost of a college education today is roughly comparable to what the cost would have been for a low-level nobleman in the Middle Ages. Most medieval people either were not allowed to go to university or couldn’t afford it.

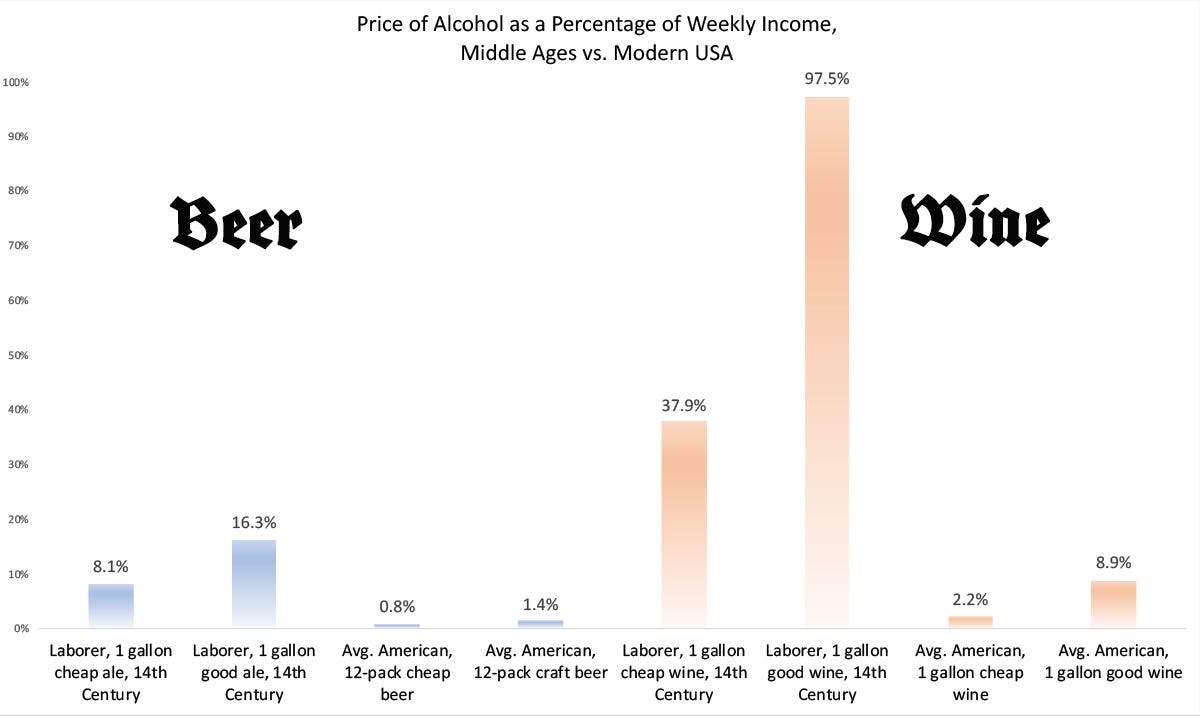

Alcohol

Bummer! Even alcohol was more expensive in the Middle Ages. That said, many people probably bought the ingredients and brewed their own ale, so these might trend higher than they actually were.

Beer/ale. Medieval prices for ale are listed by the gallon. There are 128 ounces in a gallon, so 10.67 beers. I used the price of a 12-pack, or two 6-packs in the case of craft beer, because that’s close enough. For “cheap beer” I estimated $13 per 12-pack, for craft beer $24.

Wine. Wine is also listed by the gallon. 3-4 pence for a cheap gallon, 8-10 pence for a good one. There are 5 bottles of wine in a gallon, so the US prices are for 5 bottles of wine. I estimated $7.50 for a cheap bottle, and $30 for an expensive one.

There is much more variation in the types, qualities, and prices of beer and wine today. The “best Rhenish in London” only cost about twice as much as the cheapest. Today there are bottles of wine that cost hundreds, or even thousands, of dollars, while at the same time you can a get drunk off a 40-oz. bottle of Steel Reserve for about 3 dollars.

Conclusion: Alcohol in general was more expensive in the Middle Ages, although many people probably brewed their own, which would have made it a little more affordable. Higher end wines were more affordable in the Middle Ages.

Last but not least: Taxes

Taxes are almost impossible to pin down. They varied greatly by location, changed all the time, and some people just outright refused to pay them (see: Tax Rebellions). We’ll look specifically at late 14th Century England, since that is where most of the other data above comes from.

I found wildly different estimates in researching what a person would have paid in taxes, ranging from this r/AskHistorians post claiming a rate of 40-50% in medieval to Hungary, to “they murdered the tax collector and didn’t pay anything.” This article says that taxes for a medieval peasant in Sweden were about 2% of the value of their farm in the mid-14th Century. This rose to about 15% of the value of the farm by the early 15th Century, leading predictably to a rebellion.

Ultimately, the best info I could find for late 14th Century England was equally as confusing and not all that different from the modern US.

Fifteenths and tenths. From the late 13th Century onwards, the “fifteenths and tenths” was the main form of direct taxation in England. People living in the country had to pay a 1/15th (6.67%) tax on movable goods. People in the towns had to pay 1/10th (10%). This wasn’t an income tax, but a tax on movable goods. I’m not entirely sure how this worked, but essentially people would have the value of their property assessed by tax officials and have to pay the appropriate percentage based on that assessment. I don’t know the value of various people’s personal property, so I used their incomes as a rough estimate.

Poll tax. A fixed-rate tax paid by all people, with the exception of beggars. It was levied in 1377, 1379, and 1381, the last of which helped spark the Peasants’ Revolt. The 1377 poll tax was a flat rate of 4 pence for everyone. By 1379 this had become graduated based on social standing. At the top, the Dukes of Lancaster and Brittany owed 1,600 pence (10 marks) each. At the bottom, peasants owed 4 pence (1 groat). A baron was somewhere in the middle, at 480 pence.

Tithes. Under the tithe, people contributed 1/10th of their income to the Church. For the numbers above, I’m assuming everyone had to pay the tithe.

US. While the US has multiple different types of taxes, I only used federal and state income taxes for simplicity. The high estimate is for a single person living in California, which has high state income taxes. The low estimate is for a single person living in Texas, which has no state income tax. A married couple would have paid less in both cases. Makes one wonder why so many people are moving from California to Texas…

Conclusion: Taxes in late 14th Century England were roughly comparable to taxes for the average American today.

So, what can we learn from all of this?

Honestly, not much.

Life was so much different in the Middle Ages that it’s hard to say definitively whether it was more or less affordable.

The necessities of life — having a house to live in, eating, getting married, dying, armoring a warhorse — were and are expensive. If you can avoid doing these things you might be all right.

Alas, if you’ve made it this far I hope you enjoyed reading this. If you did, please let me know in the comments. If you didn’t, then please comment, “I am a person of poor taste and did not enjoy this article. Please imprison me in the Royal Dungeon where I will live out the rest of my days in squalor with the other unfortunate souls who were foolish enough to criticize The King.”

Long live The King, etc., etc.

Main Sources

~BLS Consumer Expenditures 2021. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cesan.nr0.htm

~BLS data on average retail food and energy prices. https://www.bls.gov/regions/mid-atlantic/data/averageretailfoodandenergyprices_usandwest_table.htm

~Kenneth Hodges, List of price of medieval items, UC Davis. http://medieval.ucdavis.edu/120D/Money.html

~Shadiversity, What did medieval people do for entertainment?

I’m guessing it’s this Kenneth Hodges, who is currently a professor at Virginia Tech.

The BLS numbers are based on “consumer units,” not necessarily individual workers. From BLS: “Consumer units consist of families, single persons living alone or sharing a household with others but who are financially independent, or two or more persons living together who share major expenses.”

1 pound = 20 shillings

1 mark = 160 pence

1 shilling = 12 pence

1 groat = 4 pence

1 penny = 4 farthings

There were also various other coins and units of money, such as sixpence (6 pence), crowns (5 shillings), and ha’pennies (half a penny). Pence is confusingly abbreviated as “d”, after the Roman denarius. I’ve spelled it out instead of using the abbreviation, to avoid confusion.

From Oxford’s website: “From 1878 academic halls were established for women, who were admitted as full members of the University from 1920. By 1986, all of Oxford’s male colleges had changed their statutes to admit women and, since 2008, all colleges have admitted men and women.”

LOL-- after all that in-depth information, “So, what can we learn from all of this?

Honestly, not much.” 🤣 This was quite interesting! I think us humans and the obstacles, joys, and conundrums we face have always been the same. It’s the details that change.

It was nice filling in some of my information about the Middle Ages. From what I know of Master Carpenters, most of their work wasn't on a construction site, that was for journeyman. Most Masters were either teaching or pricing, and doing bookwork. The rest was new to me. I rather enhoyed the article, please, I have no desire to see the dungeon, Sir. ...Now I am wondering if I would prefer the Dungeon to the Oubliette...