Do You Work More Than A Medieval Peasant?

An Addendum

Dearest Reader, today’s post is a slight departure from our usual fare of satire news. It instead takes a deep dive into one of the most pressing issues of our day: peasants not toiling enough.

If thou dost enjoy these “addendum” articles and wouldst like to see more, sendeth His Majesty an email or letteth Him know in the comments.

This has been a meme for years:

Medieval Peasants Worked Less And Vacationed More Than Modern Americans Do

Average American worker takes less vacation time than a medieval peasant

Before Capitalism, Medieval Peasants Got More Vacation Time Than You. Here’s Why.

Since the never-ending toil of the peasantry has been a constant theme of Ye Olde Tyme News, I thought this was worth looking into.

My initial hypothesis is that these statements are probably misleading. There’s no way medieval peasants weren’t endlessly toiling in the fields, right? The modern conception of “a job” is likely very different from what it was in the Middle Ages, and data on medieval work hours is scarce. So I also think it will be difficult to make a useful comparison.

But let’s give it a try. We’ll seek to answer two questions addressed by the main arguments of these articles:

Does the average worker in the modern United States work more hours per year than the average medieval European peasant?

Does the average worker in the modern United States get more days off per year than the average medieval European peasant?1

We’ll also make some comparisons to modern Europe and the Western world in general. We won’t be looking at the rest of the world, where the work situation may differ greatly from the West. Maybe that’s a topic for another day.

Side note: most of the above articles acknowledge that life in the Middle Ages would have sucked in many other ways, regardless of how many hours people worked. In the authors’ defense, I don’t think any of them are arguing that we should go back to living like medieval peasants.

Part I - Working Hours

Medieval Peasants

Let’s start by looking at working hours for medieval peasants, as well as other types of medieval workers.

The main source for almost all of the “you work more than a medieval peasant” articles is the 1992 book The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure, by economist Juliet Schor.2 Most of them cite Schor’s estimate that a 13th-century English peasant worked approximately 1,620 hours per year.

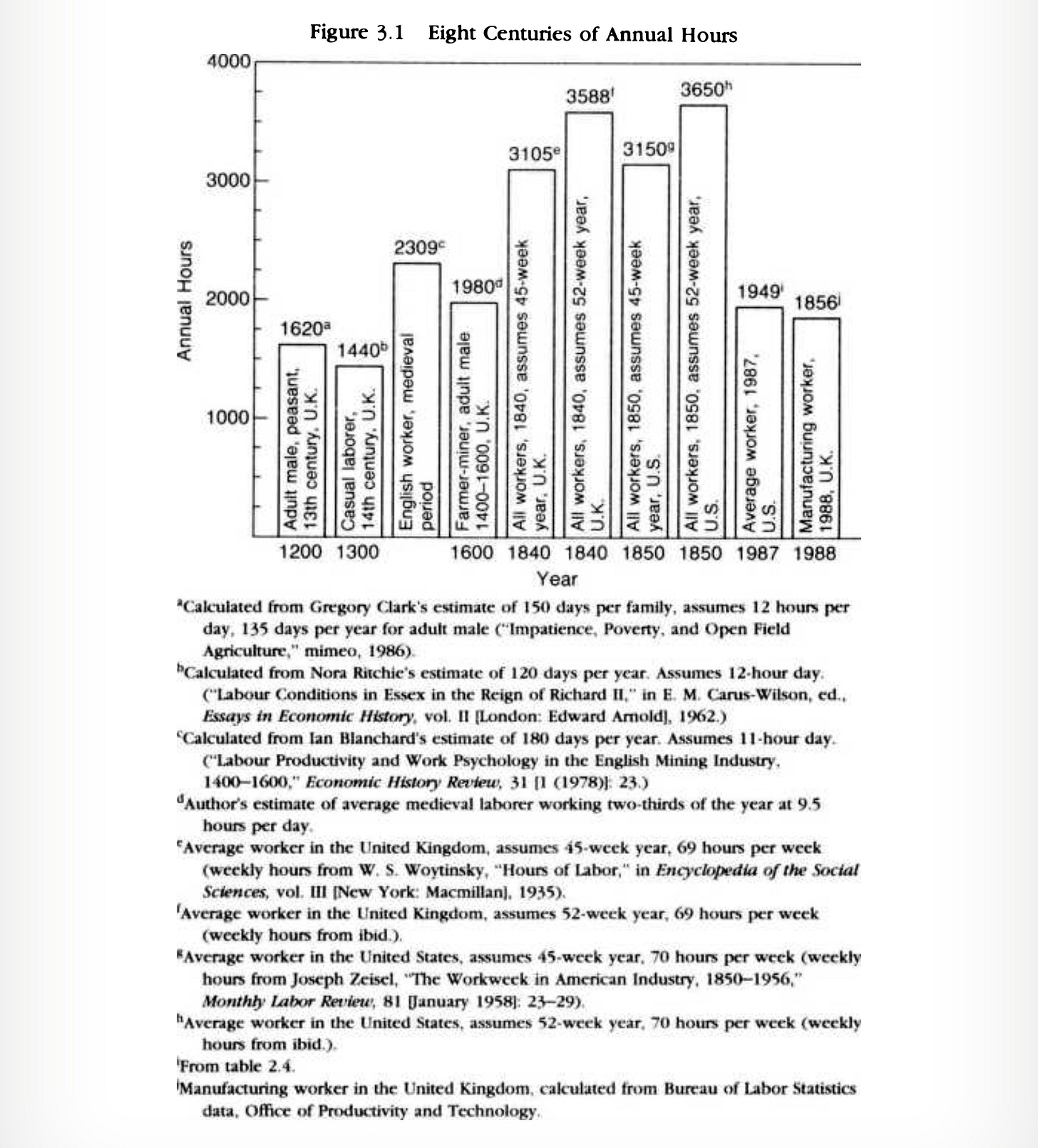

How did she arrive at that number? Here’s the chart from her book:

As you can see, the estimates for medieval work hours vary pretty widely, from a low of 1,440 hours for a 14th century “casual laborer,” to a high of 2,309 hours for an “English worker, medieval period.” Here’s a breakdown of the various numbers she gives:

1,620 hours, Adult male, peasant, 13th century, U.K. - This is based on an adult male peasant working 12 hours per day for 135 days per year. This is the number typically cited in the “you work more than a medieval peasant” articles. Note that Schor here is citing an unpublished paper by Gregory Clark from 1986. I could not find this paper and wish the book went into more detail on how Clark arrived at this number. Alas, it does not. However, this makes me skeptical of the 1,620 number.

1,440 hours, Casual laborer, 14th century, U.K. - This is the lowest estimate in the chart, based on a 12 hour day for 120 days per year. For this one, Schor mentions the “backward-bending supply curve of labor—the idea that when wages rise, workers supply less labor.” In the late fourteenth century, wages had risen following the Black Death. So many people had died that there weren’t enough people to do all the work. The people that survived could charge more, and thus didn’t have to work as much to make decent money. This number is specific to the late 14th century in the U.K. I don’t think it can be applied to the Middle Ages more broadly, and I think it is probably too low, since it’s assuming that people didn’t work at all for two-thirds of the year.

2,309 hours, English worker, medieval period - This number comes from 11 hours per day for 180 days per year. This group is not strictly peasants, but “farmer-miners,” who would spend 135 days per year farming, and around 45 days mining.

1,980 hours, Farmer-miner, adult male, 1400-1600, U.K. - This is Schor’s own estimate of how many hours “the average medieval laborer” worked. It is also labeled as “farmer-miners” rather than strictly “peasants.” She estimates they worked 9.5 hours per day for two-thirds of the year. It seems like she went somewhere in between the other numbers to arrive at this. She agrees with the 135 days per year farming number above, but I guess adds additional hours for work being done in addition to farming, in this case mining.

It’s not entirely clear to me where the overlap is between “adult male, peasant,” “casual laborer,” “farmer-miner,” and “average medieval laborer.” But I think it’s safe to assume that in addition to farming during the warmer months, most peasants also did something in winter. They weren’t just sitting at the tavern getting drunk for the other 230 days of the year (or maybe they were, in which case sign me up).

While work activity certainly slowed during the winter, there was plenty of work to be done in the colder months, even if it wasn’t their main “job” as we would understand it today. Contemporary artwork depicts peasants undertaking a variety of tasks, including slaughtering pigs, planting winter crops, chopping wood, pruning trees, repairing things around the farm, and caring for animals.

It seems that the lower estimates don’t account for any of these winter tasks. Because of this, I think Schor’s middle-of-the-road figure of 1,980 hours is probably the most accurate of these.

Another interesting source on work in the Middle Ages is The Mediæval Mason, by Douglas Knoop and G.P. Jones, which discusses the work life of . . . medieval masons. Not peasants, but it is still informative of general work schedules of the time. One observation is that wage rates for masons differed based on the season. They were highest in summer, lowest in winter, and somewhere in between during the spring and fall, implying that their work hours differed each season. Citing Masons’ Ordinances from the year 1370, working hours were:

Winter: daylight until dark, with 1 hour for dinner and 15 minutes for “drinking” in the afternoon (nice!)

Summer: sunrise until 30 minutes before sunset, with 1 hour for dinner, 30 minutes for drinking (double nice!), and 30 minutes for sleeping

Dividing the year into 5 winter months and 7 summer months, they estimate a mason would have worked an average of 8 3/4 hours per day during the winter, and 12 1/4 hours during the summer.

Masons’ daily hours seem roughly equivalent to those of peasants, namely sunrise to sunset. Although unlike farmers they continued working their primary job through the winter, albeit for shortened hours.

Both Schor and The Mediæval Mason agree that the pace of work in the Middle Ages was slow, the hours were not strict, and workers got multiple breaks throughout the day. So it wasn’t quite the back-breaking toil modern people might imagine it to be. Workers would show up late, leave early, and dilly-dally during break time. But honestly, that part is not all that different from many modern jobs.

Modern Workers

Data on modern work hours is much more accessible.

According to Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the average American worker worked 1,777 hours in 2019. The average worker in the European Union worked 1,593 hours. The busiest OECD country was Colombia, where the average worker worked 2,172 hours in 2019. Schor’s estimate is that the average American worker in 1987 worked 1,949 hours per year. This is slightly higher than OECD’s 1987 figure of 1,839 hours, but not that far off.

Among OECD members, average working hours have been decreasing steadily for the past 70 years.

Peasants vs. Americans - Working Hours

Let’s go back to our first question: Does the average worker in the modern United States work more hours per year than the average medieval European peasant?

Here’s what we have for working hours:

Medieval peasant: 1,980 hours per year

Modern American: 1,777 hours per year

Modern European Union worker: 1,593 hours per year

Modern Colombian: 2,172 hours per year

Based on these numbers, the average American works fewer hours than the average medieval European peasant, although not by much; the average worker in the EU works far fewer hours than the average medieval peasant; and the average Colombian works more.

However, taking into consideration:

there were times and places in the Middle Ages where peasants worked less (e.g., England in the late 1300s);

the pace of work in the Middle Ages may have been more leisurely than it is in many modern jobs, and maybe this needs to be factored into work hours; and

the data for medieval work hours is unreliable;

…and it’s hard to say this for certain. So what’s our answer?

The average worker in the modern United States probably works fewer hours per year than the average medieval European peasant. But I could be convinced otherwise if I had better data on medieval peasant work schedules.

Part II - Days Off

When we talk about “days off” or “vacation,” the main considerations are weekends, holidays, and seasonal fluctuations. First, let’s look at medieval workers.

Medieval Days Off

Holidays

In addition to having Sundays off, medieval people had many religious holidays in which they were not expected to work. The Church’s liturgical calendar consisted of two cycles: the temporal cycle, or feast days and seasons commemorating events in the life of Christ; and the sanctoral cycle, feasts commemorating both local and widely-known saints.

It’s hard to gauge exactly how many feast days there were, because it would have varied greatly based on the time and place. Schor cites the book Discussion of Holidays in the Later Middle Ages, by Edith Rodgers as claiming that France’s Ancien Régime guaranteed 52 Sundays, 90 “rest days,” and 38 holidays in which people didn’t have to work, which means they would only have had to work about 185 days per year.

She also notes that there were many “ales,” or ale-drinking feasts to celebrate various events. Lamb-ale was a party to celebrate the time of lamb shearing, hock-ale or Hocktide celebrated the Monday and Tuesday after Easter, and scot-ale has a number of interesting interpretations which are worth listing here:

A drinking party, prob. compulsory, held by a sheriff, forester, bailiff, etc., for which a contribution was exacted

A festivity held by a church to raise money

A drinking party given for the villagers by the lord after mowing

The keeping of an alehouse by an officer of a forest, and drawing people to spend their money for liquor for fear of his displeasure3

People had the day off for scot-ale, but they were forced to go to the sheriff’s drinking party to give him money for booze. On the bright side, at least their lawns were already mowed.

This post thinks there were about 45 feast days in medieval England in the year 1200. Among them are everybody’s favorites of St. Barnabas’ Day, the Beheading of St. John the Baptist, and Martinmas, when everyone comes together to butcher the “Martinmas beef.” Accounts from 1444-45 and 1445-46 during the construction of Eton College seem to confirm this number. They list 46 different days observed as feast days each year.4 However, as many of these feast days fell on a Sunday, workers only had off 38 and 43 feast days, respectively.

Weekends

Pretty much everybody had Sunday off.

As for Saturdays, it’s unclear to me whether peasants worked or not. Sundays and feast days are explicitly listed as days off in the sources, but Saturdays are not. So my assumption is that they usually worked at least a partial day on Saturday unless it was a feast day.

Sources about Saturdays are a little better for masons, and are recorded in some regulations of the time.5 Saturdays were half days for some masons, others worked full days on Saturdays, others didn’t work at all, and some even picked up overtime or night shifts.

My best guess is that the medieval work week for most people was more of a five-and-a-half day week rather than the five-day week that is common today.

Seasonal Changes

Work slowed in the winter, as mentioned above. Peasants still had things to do, but their schedules were less regular, and they likely took extended time off around Christmas and in January when it was particularly cold. Masons worked shorter days in the winter due to shorter days and colder temperatures. As with the “farmer-miners” mentioned above, it’s possible some peasants picked up other work during the winter months, in addition to their various tasks around the farm, but all of the sources seem to agree that work hours during the winter were greatly reduced.

Bottom line: It’s hard to get an accurate estimate of the average days per year a medieval person worked versus how many they had off, since it varies so widely, but some best guesses are:

Low extreme: 120 days of work per year - From Schor’s chart above, this is for a “casual laborer” in the late 14th century in the U.K., when people could afford to work shorter hours due to higher wages. Such a peasant would only work during the peak summer/farming season, and take off all Sundays and holidays, and possibly Saturdays.

High extreme: 240-250 days of work per year - From The Mediæval Mason, this would be for a mason who works year-round, has Sundays and holidays off, and works half days on Saturdays. Maybe he occasionally picks up overtime if there’s a big building project going on. (His days off would be: 52 Sundays, 40-45 holidays, 52 half-Saturdays).

Middle estimate: 180 days of work per year - I think it’s reasonable to say that the typical peasant throughout the Middle Ages was somewhere in between the two numbers above. This schedule would look something like:

Work 135 days during the spring/summer/fall

Off for all 52 Sundays

Off for 40-something holidays

Work half-days every Saturday

Work a reduced schedule in December and February

Off all of January when everything is frozen

Modern Days Off

Sure, most Western countries no longer offer 46 Church-dictated feast days, or days when the local forest bailiff coerces everyone into ditching work to come drinking with him (although, if I’m ever elected bailiff, I promise to reinstate this). We do, however, have government holidays.

Currently, the United States recognizes 11 federal holidays. Additionally, most modern Americans do not work on the weekends. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 33.4% of American workers worked weekends in 2019. That’s pretty high, but still a minority.

There’s also paid time off (PTO). While the US is the only country in the OECD that does not mandate paid vacation, the average American worker took 17.2 days of PTO in 2017.

The year 2022 has 105 weekend days and 10 U.S. federal holidays (New Years’ Day was observed on Dec. 31, 2021). If you subtract these, there’s 250 working days this year in the US. Subtract the 17 days of PTO taken by the average American worker, and the average American works about 233 days per year.

Elsewhere in the world:

Austria leads OECD countries with 38 total days of statutory paid leave, according to Statista (25 days annual leave, 13 public holidays)

France and Spain are tied for second with 36 days each

I know I said we wouldn’t talk about other modern countries, but according to Wikipedia, the countries with the most public holidays are Cambodia and Iran, with 27 days each. Lebanon is also up there with 22 public holidays

Peasants vs. Americans - Days Off

Now to answer our second question: Does the average worker in the modern United States get more days off per year than the average medieval European peasant?

Average medieval peasant: 180 work days, 185 vacation days

Average American: 233 work days, 132 vacation days

Average European: It varies. Most probably work fewer days than an American but more than a medieval peasant

Answer: No. The average medieval European peasant had more days off per year than the average worker in the modern US.

I’m more confident in this answer than on the answer to the first question. There are medieval calendars and more contemporary data on feast days and holidays than there are for work hours in general. So on this count, I’d say the meme is actually correct.

What did medieval peasants do on their days off? They couldn’t really go on “vacation” in the modern sense of the word. Some of these days, according to Schor, were likely spent in sober churchgoing, while others were spent feasting and drinking. It’s also possible that some of them worked overtime, performing holiday and night work.

Another question to ask is whether workers were paid on their days off. This seems to have varied. Among masons, they would often receive reduced pay on feast days. According to regulations from York in 1352, if two feast days fell in the same week, the mason lost one day’s pay; if three feasts fell in the same week, they lost half a week’s pay.

Also, the fact that medieval holiday calendars might include pictures of peasants working does not inspire confidence that they always got the day off as planned:

Part III - Conclusion

Here’s what we’ve discovered:

Does the average worker in the modern United States work more hours per year than the average medieval European peasant? No. The average medieval peasant probably worked slightly longer hours per year than the average American. However, there is a lack of solid data so I’m somewhat skeptical of this conclusion.

Does the average worker in the modern United States get more days off per year than the average medieval European peasant? No. The average medieval peasant got more vacation days than the average American does.

It seems counterintuitive that Americans work more days but fewer hours than medieval peasants. But this can be explained by the length of the average work day. Peasants worked sunrise to sunset. On days that they work, the average American full-time employee works 8.5 hours per day. Americans work more but shorter days. Peasants worked fewer but longer days.

Which situation is better? There’s certainly something to be said of the peasant pace of putting in long but leisurely days when there’s work to be done, and not working at all when there’s not. I’m also a big fan of having more holidays, and will gladly support any government proposals to host more scot-ales.

But I think I’d still rather be a modern American worker than a medieval peasant, even if I don’t get a day off for the Feast of St. Barnabas or a drinking party with the sheriff every time I mow my lawn. At least we’re allowed to quit.

For the most part, the numbers for medieval workers in this article only apply to males, since the data does not include the types of jobs females would have been doing at the time. However, they’re often depicted in medieval artwork working alongside men. If you include raising children and taking care of the household, my guess is medieval females worked longer hours than their male counterparts.

Note that comparing modern Americans to medieval peasants is not the main idea of this book, and it only uses them as one example of how work has changed over time.

The first three definitions are from the University of Michigan Middle English Compendium. The last is from Wiktionary.

Douglas Knoop and G.P. Jones, The Mediæval Mason, Manchester University Press, 119-120. https://socialsciences.mcmaster.ca/econ/ugcm/3ll3/knoop/MediaevalMason.pdf

Ibid., 120-121.

Thanks for this analysis! I've long been skeptical of the "you work more than a medieval peasant" meme, if only because I grew up in a rural farming area, and can definitively say that farm work never really stops. It doesn't matter if it's Sunday or a feast day, if you keep animals you'll have to tend them every single day. You could definitely take a day off from planting, or postpone harvesting for a bit, but so many farm tasks are unrelenting. You'll milk every day, or you'll hurt the cows. You'll have to put the chickens in their coop every night or risk losing your chickens. I love that the stone masons kept such good records, though. It feels so on brand for stone masonry.

Chores

The average America works many hours a week to have those chores done for them, or have machines that do them, so those need to be included. They ground flour every day by hand for cooking. They didn’t have a wood pile, so most every day they had to gather branches, dung, and twigs, commonly from some place over a mile away for cooking. With few clothes, laundry was done in a bucking by hand nearly every other day. Cooking from scratch also took hours every single day. The tools were soft iron, so every day after working in the field, you spend an hour that night sharpening them for the next day. Then there was the almost daily mending, changing the thrush light, sweeping out the place out of the stuff blown in by the wind and your dinner crumbs. A medieval peasants day did not stop when work was over, far from it. And no order of the church relieved him from taking care of those chores. He would commonly spend more of his time doing those chores than “working.”