‘Tis Not Fair That Fools Get Their Own Holiday But I, A Wiseman, Get Nothing

Jester's privilege gone too far

By Erwygge the Wise

Despite my great wisdom, I enjoy a hearty jest as much as the next fellow. Indeed, I hath even been known to pull a prank or two on All Fools’ Day. (During my lectures, I once farcically attributed a quote about prudence to The Prophecies, when it was clearly taken from the treatises of Ildibad the Hermit, much to the cachinnation of all present!)

But whilst all the Realm gets ready to celebrate Fool culture on April the 1st, one cann’t help but wonder: why do Fools get their own holiday when Wisemen like me get naught?

Are learnéd intellectuals such as mineself not worthy of such an honour?

Doth centuries of Wisemen’s contributions to society amount to nothing?

I’ve spent many a tedious year pondering theorems and conjectures, and countless grueling hours devising astute stratagems, but apparently all of mine enlightened meditations are worth not even score and four hours to the rest of mankind. All of mine efforts in awing the ignorant rubes of society with my massive intellect are apparently meaningless to those who designate our holidays. Yet, where would we be without men such as I to ponder and ruminate? I’d like to see a mere Fool ponder theorems even half as well as I.

I begrudge not the Fools for the honour that hath been bestowed upon them, this right to caper and jape prodigiously without fear of repercussion for an entire day. But theirs is not the only profession in the Kingdom deserving of such a privilege.

I think us Wisemen are also owed the distinction, a Wisemen’s Hist’ry Month or International Wisdom Day, wherein the cultural and historical contributions of noble philosophers and cultivated sages are celebrated by all the land. On this day, the Wisest Men in the Realm shall gather in the publick squares and endlessly spout information to impress one another with our superior knowledge.

Now that sounds like fun.

And, of course, womyn won’t be invited.

Addendum: Jester’s Privilege

One thing that distinguished a court jester from a mere foolish entertainer, according to Fools are Everywhere by Beatrice K. Otto, was their role as an advisor to and critic of powerful people. They would use humor to criticize that which was otherwise off limits to criticism, often moderating rulers’ behavior in the process. Openly ridiculing kings and emperors was a dangerous game, and people who did so could be severely punished for it. At the same time, in a world full of fawning yes-men, it could be beneficial to the king to hear someone tell it like it was.

Hence “jester’s privilege,” ostensibly the right of a jester to exercise free speech without fear of punishment. I couldn’t find any primary source from around the Middle Ages that listed jester’s privilege as a formal law, but it does seem to have existed, at least as a customary or informal law, in many historical times and places. People sort of knew it was a thing, even if it wasn’t written down anywhere.1 Much medieval law was based on custom, so this is not out of the ordinary. Because jester’s privilege is a form of free speech, perhaps it was seen as an extension of that right in places where free speech existed in limited form.

Nevertheless, jester’s privilege or not, jesters were often punished for pushing their jokes too far. Whether their “privilege” would protect them or not largely depended on the whims of their ruler, and the egos of the nobles their jokes were directed at. According John Doran in The History of Court Fools, it wasn’t always the king who would call for a jester to be punished, but the people who couldn’t take a joke:

“…it was the thin-skinned and thick-headed who were the first to take offence, and to call for punishment on the offender.”

Even today, in a world where people’s right to express themselves is probably the freest it has ever been in human history, comedians can still be punished for telling the wrong joke. There’s probably an evolutionary psychological reason why we get offended by jokes, and why we often seek to punish the offender, even if they meant no harm. There’s also probably a version of Godwin’s Law at work here, where as a joke becomes more popular, the probability someone will become offended by it approaches 1. Modern jesters’ audiences, connected by the internet and TV, are much bigger than those of days past, so I’d guess it’s even more likely a modern comedian will be rebuffed than a medieval one.

I don’t think this is necessarily a good or a bad thing. It’s certainly nothing new. Some jokes are offensive to some people. Any blowback is merely a norm-enforcing feedback mechanism to tell the jester when a joke went too far. It is a problem, however, when the response is grossly disproportionate to the offense (e.g., a jester makes a joke about the king’s butt so the king has him beheaded; a comedian does one off-color joke and her career is ruined). A jester’s role was to test the limits of what was acceptable to say, in the process attempting to change their rulers’ behavior for the better (or what, in their opinion, was better), using humor as a tool to soften the blow. A modern comedian’s role is much the same, except that their audience is not just kings and emperors, but pretty much anyone; the target of their jests is not just court politics, but any topic one can imagine.

Occasionally they’ll get it wrong. That’s no reason to send them to the chopping block.

Here’s a few historical examples of jesters who were punished, or nearly punished, for their jests.

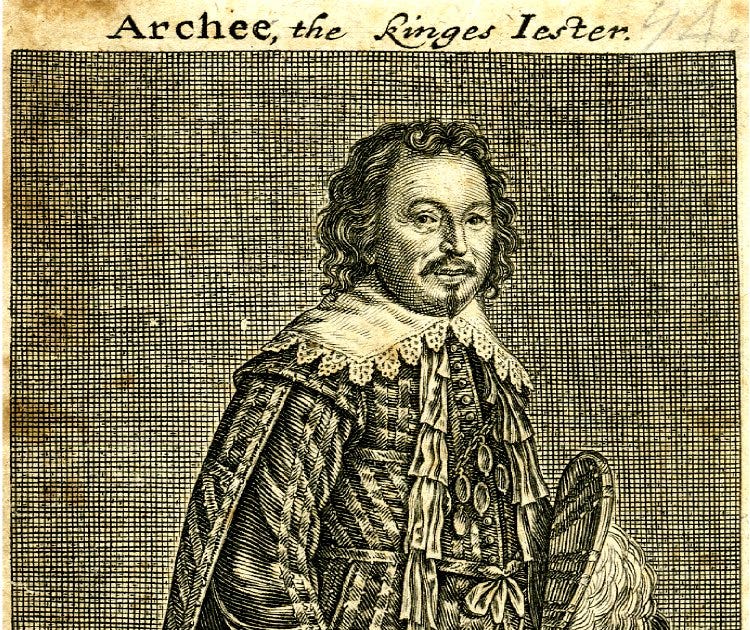

1 - Archibald Armstrong

After a relatively successful career as a sheep stealer, Armstrong became a jester at the court of King James VI of Scotland. Archy was popular and a favorite of the king, and authored the joke collection A Banquet of Jests.

One common target of his jokes was a bishop named William Laud. Laud was only five feet tall, and it seems Armstrong frequently made short person jokes about him. In 1637, he pushed it too far. Laud complained to the king, and Armstrong was sentenced "to have his coat pulled over his head and be discharged the king's service and banished the king's court."

Armstrong was banished from court, but he ultimately got the last laugh. Laud was arrested in 1641 and executed in 1645 during the English Civil War. After Laud’s arrest, Armstrong published a hit piece on him called Archy's dream, sometimes iester to His Majestie, but exiled the court by Canterburies malice with a relation for whom an odd chaire stood voide in hell:

You which the dreame of Archy now have read,

Will surely talke of him when he is dead:

He knowes his foe in prison whilst that hee

By no man interrupted but goes free.

His fooles coate now is far in better case,

Then he which yesterday had so much Grace:

Changes of Times surely cannot be small,

When Jesters rise and Archbishops fall.

He died on his estate in northwest England in 1672.

2 - Tenali Rama

Rama was a jester, poet, scholar, etc. in the court of Indian King Krishnadevaraya (r. 1509-1529). In one story, again taken from Fools are Everywhere, Rama convinced the king’s guru to carry him around on his shoulders. When the king saw this, he ordered his guards to go beat up the man on the guru’s shoulders for humiliating the guru like that. Rama saw the guards coming, and convinced the guru to switch places with him, so that, when the guards arrived, they beat up the guru instead. The king thought this was so funny that he made Rama his jester.

According to Wikipedia, Rama also authored serious religious works before dying in 1528 of a snakebite.

3 - Triboulet

Triboulet, born Nicolas Ferrial, was a jester to the French kings Francis I (r. 1515-1547), and possibly Louis XII (r. 1498-1515).2 He suffered from a medical condition that caused him to have multiple physical deformities, including a smaller-than-normal head and a hunchback. He also dressed and acted eccentrically.

He was a real person, but was also a character in many works of fiction, so it’s likely that many of the stories about him are made up. In a probably apocryphal story from Wikipedia3, Triboulet once spanked King Francis I on the butt. Outraged, Francis said he would have him killed if he couldn’t think of an apology more offensive than what he had just done.

"I'm so sorry, your majesty, that I didn't recognize you!” Triboulet responded. “I mistook you for the Queen!"

Francis was already in a bad mood and he didn’t like it when people made jokes about the Queen, so he decided Triboulet had to die. But, because of Triboulet’s years of service to him, he let him choose his manner of death. Wisely, Triboulet chose old age. The king acknowledged his clever response and merely exiled him, where he did in fact die at the then ripe old age of 57.

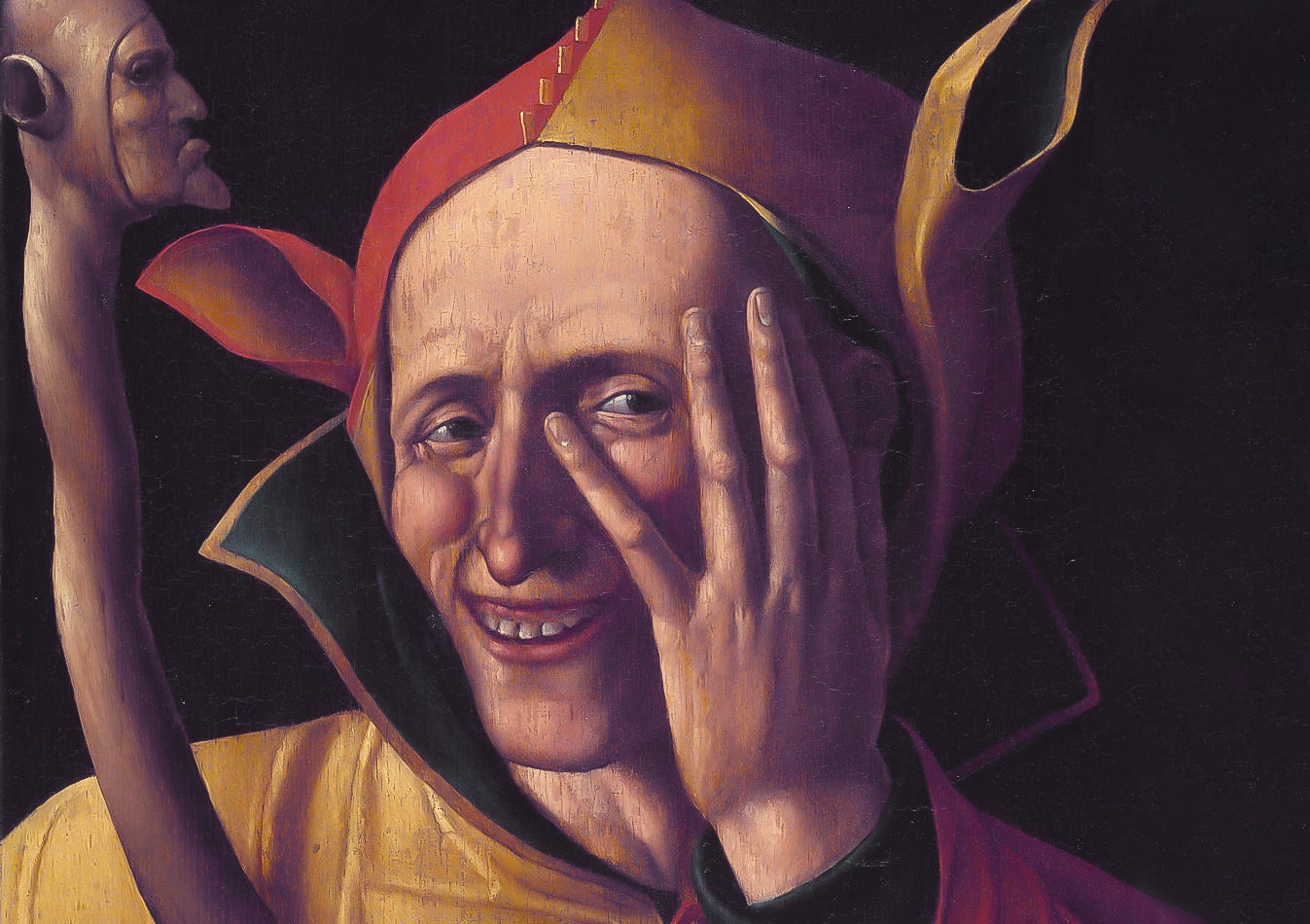

4 - Gonella

Gonella served as jester to Borso, the Duke of Ferrara in the mid-1400s, according to Doran.

Borso was “a coarse fellow, who savoured coarse jokes,” so Gonella rightly supplied him with boorish, practical jokes.

But his practical joking eventually caught up with him. One day, Borso fell very ill. The doctors said that only a sudden fright could cure him, but Borso was such a terrifying leader that everyone was afraid to try to frighten him. Except his jester.

While the two of them were taking a walk, Gonella surprised him and pushed him into a lake. The fright did indeed cure Borso, but he was so mad about being pushed into the lake that he exiled Gonella from Ferrara and said if he ever stepped foot on Ferrara’s soil again he’d kill him.

Gonella went into exile for a few months but eventually decided to return. During his return journey, he filled a cart with soil from Padua, and rode into town on top of it. When Borso’s men came to arrest him, he told them he wasn’t on the soil of Ferrara, but on that of Padua. This was a ridiculous thing to say so they arrested him anyway. But instead of killing him, Borso decided just to scare him: “a fright for a fright.” He told the executioner to put his head on the chopping block, but when the time came to behead him, to put a small drop of water on the back of his neck instead of the axe.

When execution time came around, the crowd was gathered and Gonella’s head was on the chopping block. They ran through the whole ceremonial execution stuff as if it were actually going to happen, but when it came time to complete the act, the executioner put a single drop of water on the back of his neck.

The crowd erupted with laughter. Gonella did not. He died right there on the chopping block, probably from the fear and stress caused by the ordeal.

5 - Baraballo and Querno

Pope Leo X (Pope from 1513-1521) was said to be a big fan of jests. He had a number of jesters, among them Baraballo and Querno. One of the two once participated in a burlesque version of a Roman triumph at Leo’s behest, parading through the streets of Rome on the back of Leo’s pet white elephant Hanno, and at the end was crowned in a mock ceremony. However, whenever his jesters told a bad joke, Leo would have them viciously bastinadoed (the soles of their feet would be caned).

6 - Jeffery Hudson, aka “Lord Minimus”

Hudson was a court dwarf to English queen Henrietta Maria. He fled with her to France during the English Civil War where he killed Will Croft, the queen’s master of the horse, in a horseback duel by shooting him in the head. By this point in his life, Hudson apparently no longer desired to be an object of jokes about his height, and Croft might have offended him with such a joke. This became an international incident and Hudson was sentenced to death. But the queen interceded on his behalf and his life was spared.

Wikipedia says he was later captured by Barbary pirates and was a slave laborer in Africa for up to 25 years. This sounds pretty ridiculous, and I might have to read into it more and write something about Lord Minimus in the future. At some point he made it back to England where he eventually died, possibly as a prisoner at Gatehouse prison.

7 - Stone

Not much is known about the jester named “Stone,” but he’s mentioned in John Selden’s Table-talk, where he’s “whipt” by the Lord of Salisbury for telling an anti-Lord of Salisbury joke. (Actually, he just called him a “Fool”).

8 - Gallienus’s Jesters

Gallienus (r. 253-268) was emperor of Rome together with his father Valerian, until Valerian was captured in battle by the Persians. While Valerian was a captive, a large number of Persian war prisoners was paraded through Rome. Multiple jesters crossed through the crowd and deliberately scanned the faces of each prisoner, then left without comment. Gallienus, expecting them to make a joke, asked what the meaning of this was. They told him they were looking for his esteemed father Valerian among the Persians, but couldn’t find him.

Gallienus did not take this joke well. He had the jesters all bound together and burned alive.

9 - Peter the Great’s Jesters

Russian Tsar Peter the Great (r. 1682-1725) kept over a hundred jesters of all types, according to Doran. For the most part, however, it seems like the jesters themselves were often the objects of ridicule. Their role gives less of a “use humor to comment upon society and politics” and more of a “make me laugh or I’ll kill you” vibe.

To some jesters Peter would give fake titles such as “King of Siberia” and have them dine with him in this role, usually making jokes at their expense or physically abusing them.

On one occasion two men were arrested for a crime but pled insanity. Peter, rather than have them executed, ordered them to become his jesters, but only on the condition that they act insane for the rest of their lives like they said they were in the trial. He held them to this, and after years of constantly pretending to be insane they both actually went mad.

A parting thought about jesters:

“Why, pray, of late do Europe’s kings

No jester in their courts admit?

They’ve grown such stately solemn things;

To bear a joke, they think not fit.

But though each court a jester lacks,

To laugh at monarchs to their face,

All mankind do behind their backs,

Supply the honest jester’s place.”4

The History of Court Fools, by Dr. John Doran quotes a certain “Pepys’ Diary” from 1667-1668 as mentioning a jester named Tom Killigrew, who had a contract of sorts that appointed him as the “King’s Foole or Jester,” in which position he “may revile or jeere anybody, the greatest person, without offence, by the privilege of his place.” So it’s possible some kings issued this right to jesters on a contract-like basis.

This book also mentions jester’s privilege in many places going back to the days of ancient Greece.

Wikipedia says he was a jester to both. Doran says he was only a jester to Francis I.

I couldn’t find the original source for this story, but it’s a good story even if fiction.

Quoted in The History of Court Fools. I don’t know where the original quote comes from, possibly Doran wrote it.