How to Exact Tribute from Thy Vassal States Without Being “That Guy”

'Tis possible to exact tribute without being so lame about it

E’ery subjugated territory knows him. He rides ‘round his conquered demesnes putting on haughty airs atop his garish white steed. Underlings everywhere roll their eyes when he dismounts and reads the outlandish list of villeins that must pay him now in gold or be sent to the gallows.

‘Tis “that guy,” and no lord wants to be him. His subjugating style is clearly taken from some “Overlording for Knaves” book. He knows not what a churlish saddle goose he’s being, and is totally unawares of his noble ridiculousness. Any self-respecting patrician must avoid being him at all costs.

Here’s the proper way to exact tribute from thy vassals states without being “that guy.”

Keepeth it Simple

There be no need for opulent displays of thy wealth and authority when collecting payment from thy dependencies. Nor is there a need for grandiose proclamations of thy magnificence upon thy arrival in town. Thy vassal states know how much tribute they owe thee, and they know thou art so much more magnificent than they could ever be. Don’t rub it in.

Keepeth It Professional

After a long journey to the lands of the Frynnfólk along the border, thou mayest be tempted to fraternize with thy subjects, or even exercise primæ noctis on their chieftain’s betrothed (as is thy right!). But there is a tyme for collecting tribute, and a tyme for other types of ritualized oppression. Stickest to the task at hand and focus on the tribute.

Be Flexible Enough to Accept Payment in Other Types of Jewels and Precious Metals

Many of thy client domains are but humble folk, with scant access to the vast amounts of gold thou demands for thy coffers. At the same tyme, many of their lands are rich in rare ores and gemstones. Be flexible enough to accept payment in rubies, silver ingots, pearls, or jasper. Just don’t forget to charge the extra “Other Types of Jewels and Precious Metals as Tribute” Tax.

Addendum: Men (and Women) Who Row

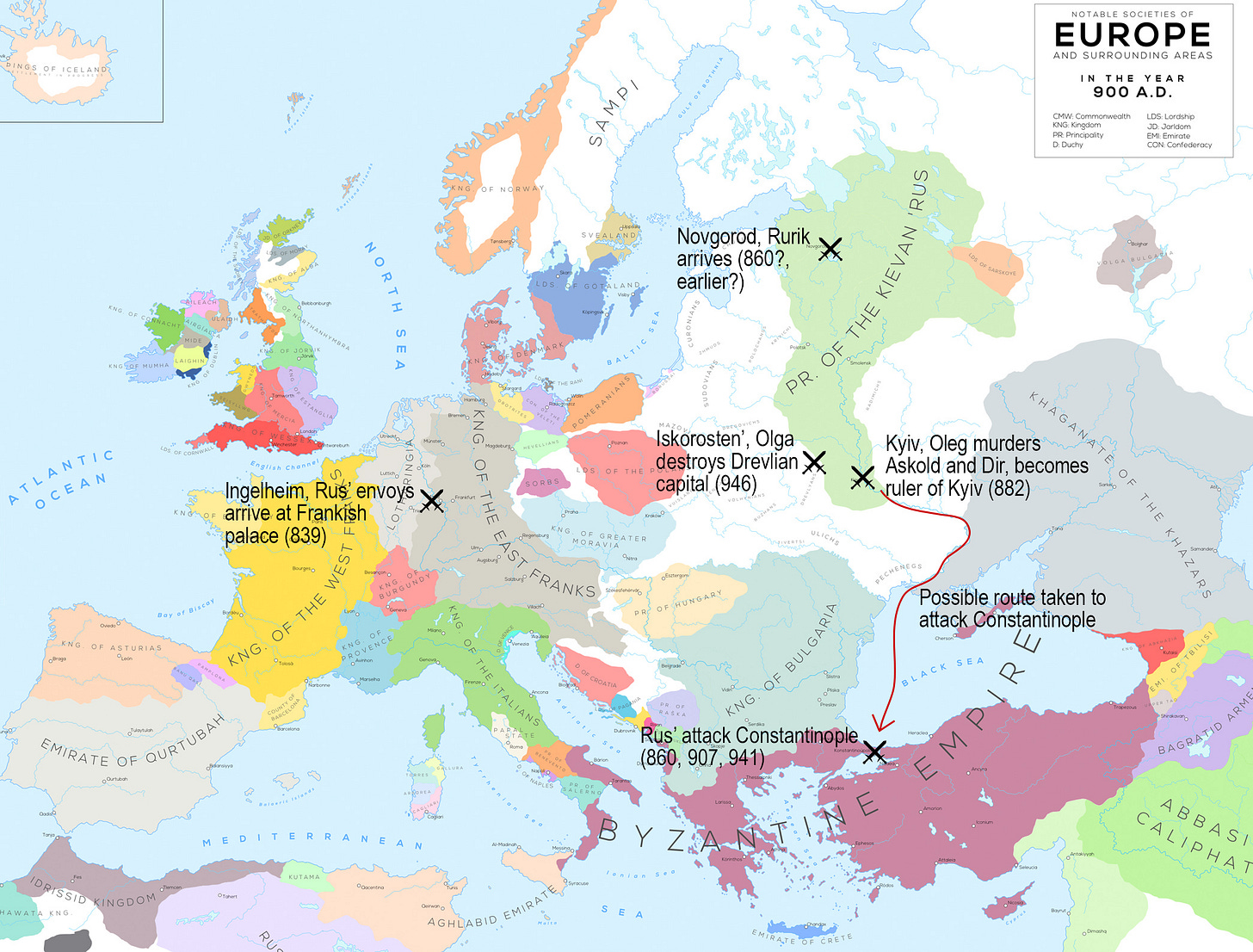

In June of the year 860 AD, a fleet of 200 ships sailed through the Bosphorus and attacked the Byzantine capital of Constantinople. Emperor Michael III was away fighting a war against the Arabs in the east, and the city was caught unprepared. Though the attackers weren’t able to breach the city walls, they pillaged the suburbs and surrounding islands. The raiders were a people called the Rus’, and the greatest city in the world narrowly avoided being overrun, but not before the attackers inflicted much carnage. (It is unclear if their ships were destroyed in a storm, they were defeated in battle somewhere, or they otherwise just decided to leave.)

The first appearance of the Rus’ in recorded history occurs when two envoys arrive at Ingelheim to the court of Louis the Pious, Charlemagne’s son and King of the Franks, in 839. They’re accompanying a group of Byzantine envoys, who request that the Franks give them safe passage back to their homeland in the north. They had originally come to Constantinople via a different route, but are afraid of being killed by barbarian tribes if they return along that route. Louis, suspecting them to be spies, instead has them arrested. It’s unknown what happens to them after that.

The Tale of Bygone Years—also known as the Rus’ Primary Chronicle, the Russian Primary Chronicle, or just the Primary Chronicle—was compiled by a monk named Nestor in Kyiv in the early 12th century. It chronicles Kyivan Rus’ from roughly the mid-800s to about 1100.

The sources about the early Rus’ are not always reliable. Even who exactly the Rus’ people were is still debated among historians.1 The most widely accepted view is that they were Scandinavians—aka Vikings, referred to as “Varangians” in most contemporary accounts—but over time it seems that “Rus’” also comes to include numerous other peoples that were allied to or associated with the Varangians. The Rus’ play a significant role in the histories of the Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian people, but reader be warned: attempts to justify geopolitical motives by harkening back to the good old days of the Rus’ are typically just propaganda.

One theory about the name Rus’ is that it comes from an Old Norse word that has to do with rowing or naval conscription, sometimes translated as “men who row.” I’m not sure how reliable this translation is, but it does sound really cool.

In any case, they certainly produced some interesting leaders. Here’s a few from the earliest days of the Rus’. Most of this is taken from the Primary Chronicle, so consider it to have elements of actual historical events mixed in with a healthy dose of legend and lore.

1. Rurik

The first Varangian ruler of Novgorod. The Primary Chronicle says the local people ousted the Varangians from their land in 859.2 But then there was discord among the different tribes, so in 860-862 they invited the Varangians back to rule over them. My guess is this probably doesn’t tell the whole story, because nobody just goes to some outsiders and says “come rule us” unless there’s a pretty dire reason to do so.3

Anyway, they invite Rurik and two of his brothers to rule over different areas around Novgorod. When the two other brothers die, Rurik becomes the sole ruler.

The Primary Chronicle doesn’t say much else about Rurik, except that he dies sometime between 870-879 and bequeaths the land to his kinsman Oleg, because his son Igor is still a child.

Confoundingly, there is another much better known Viking named Rorik who is doing Viking stuff around Western Europe throughout the 9th century. He rules Friesland in the Netherlands for decades, but disappears from the Western European histories for a few years right around the time that Rurik shows up in Novgorod. There are theories that they might have been the same person, although the general consensus is that they were not.

2. Askold and Dir

Two Varangians who live under Rurik’s rule. In the early 860s they request his permission to travel to Constantinople (referred to in the Primary Chronicle as “Tsar’gard” or “Tsargrad”: “City of the Emperor/Tsar”; also called “Miklagard” in Old Norse: the “Great City”), and he grants it. They travel down the Dnieper River with their families and see the city of Kyiv on a hill overlooking the river. The locals tell them the city currently pays tribute to the semi-nomadic Khazars. The Primary Chronicle doesn’t go into much detail on the matter, but it says that Askold and Dir gather some of their followers and become rulers of Kyiv.

The Primary Chronicle says Askold and Dir lead the attack on Constantinople in 866. Byzantine sources are probably more reliable and say it occurred in 860. In that year, the Rus’ pillage the island of Terebinthos (modern Sedef Island, Turkey). Ignatios, the former Patriarch (head religious figure) of Constantinople, is living in exile there after having been forced to resign in 858. His biography says the Rus’ raided the island, looted his monastery, and dismembered 22 of his servants with axes. When the authorities in Constantinople hear of this, they’re apparently upset that Ignatios didn’t get dismembered as well.4

It might have been someone else that led the attack, but Askold and Dir are the most likely candidates. The timeline and geography would make sense if they established their rule in Kyiv in the 850s or before (earlier than what the Primary Chronicle says), built a fleet, then sailed south down the Dnieper into the Black Sea and then to Constantinople in 860.

Most of the Byzantine army and navy were away fighting the Arabs to the east, including Emperor Michael III (unrelated, but his epithet was the Drunkard). The navy was also fighting other Vikings in the Mediterranean. Going back to the theory of Rorik-Rurik above, that the Rus’ happened to attack precisely when the city was almost completely undefended opens it up to speculation that it might have been coordinated between the Rus’ and other Vikings to the south, or even with the Arabs. This would fit nicely with the Rorik-Rurik theory, if there was one Rorik-Rurik mastermind coordinating Viking attacks all around Europe. This is just speculation and is by no means accepted among historians, but is interesting to think about.5

There’s not much more info about Askold and Dir until 882 when they’re murdered by Oleg (see below) and buried outside Kyiv. There’s still a park in Kyiv called Askold’s Grave, which contains a church built on the spot where Askold is thought to be buried. (According to the Primary Chronicle, Dir also was buried nearby and had a church built on his grave. Unfortunately, his either no longer exists, or if it does then it didn’t get a Wikipedia page. There’s also speculation that Askold and Dir were one person, but enough on them for now.)

3. Oleg

When Rurik dies, his son Igor is still a child, so Oleg6 becomes ruler. He brings Igor under his wing and serves as a sort of mentor-in-the-Viking-ways to him.

At this point, Novgorod is still his capital. Kyiv is ruled by Askold and Dir, but not for long. Around 882, Oleg brings an army to Kyiv and has them hide outside the city. He uses trickery to lure Askold and Dir to where his army is hiding and murders them. Now he’s the ruler of Kyiv, and this can probably be considered the beginning of Kyivan Rus’ proper. In subsequent years he goes on to make multiple other tribes in the area pay tribute to him. Among them are the Drevlians, who will feature prominently in Igor’s and Olga’s stories below.

Somewhere in the years 904-907 Oleg attacks Constantinople. The Primary Chronicle says he has 2,000 ships, but that’s probably a gross exaggeration. The attack:

They waged war around the city, and accomplished much slaughter of the Greeks. They also destroyed many palaces and burned the churches. Of the prisoners they captured, some they beheaded, some they tortured, some they shot, and still others they cast into the sea. The Russes inflicted many other woes upon the Greeks after the usual manner of soldiers.

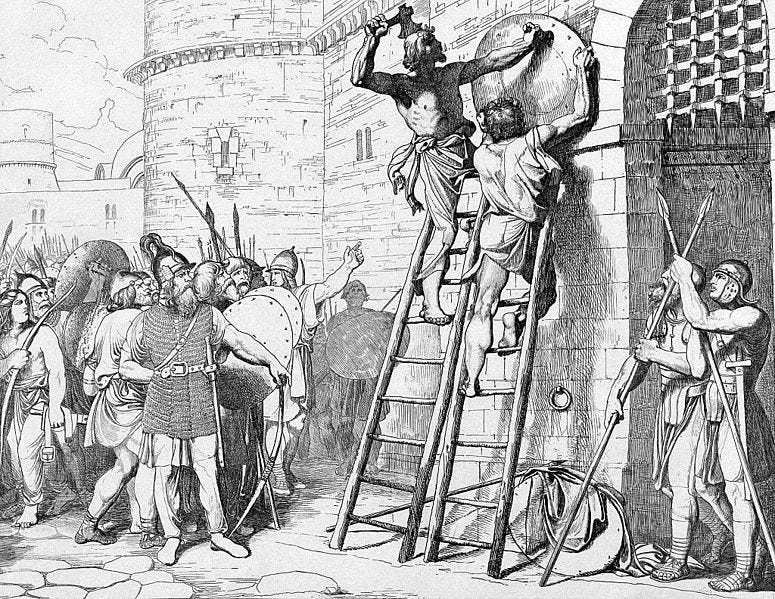

They aren’t able to breach the walls, but Oleg purportedly nails his shield to the city’s gate. The Byzantines then try to trick Oleg with a peace offering of poisoned food and wine, but he doesn’t bite. He ends up collecting tribute from Byzantium and settling a treaty that allows the Rus’ to trade there in the future.

Despite his penchant for raiding and murdering pretty much everyone he crosses paths with, Oleg seems to be regarded as a generally respected leader.

The most interesting thing about him is the way he dies. A soothsayer tells Oleg that his favorite horse will be the cause of his death:

Oh Prince, it is from the steed which you love and on which you ride that you shall meet your death.

Oleg decides never to mount the horse or even look at it ever again. Five years go by, and he remembers the story about the horse bringing about his death. He asks his squire what ever happened to that horse that was supposed to kill him, and the squire informs him it has died. Oleg laughs mockingly at the soothsayer that predicted his death:

Soothsayers tell untruths, and their words are naught but falsehood. This horse is dead, but I am still alive.

He tells the squire to lead him to where the horse’s bones are. The Chronicle continues:

He rode to the place where the bare bones and skull lay. Dismounting from his horse, he laughed and remarked, "So I was supposed to receive my death from this skull?" And he stamped upon the skull with his foot.

Sure enough, a serpent crawls out, bites his foot, and he dies.

4. Igor

Son of Rurik. He becomes ruler after Oleg’s death around 913. As per tradition, in the early 940s he attacks Constantinople. The Byzantines fight off the Rus’ fleet using Greek fire. Igor sends another fleet to attack in 944-945 and this time the Byzantines opt to sign a treaty with him rather than fight.

After the treaty with Byzantium, still in the year 945, Igor marches an army to the land of the Drevlians (or Drevylians/Derevlians) to exact tribute. The Drevlians were a Slavic tribe that lived in what was nominally the territory of Kyivan Rus’, but they had stopped paying tribute to Igor some years earlier and instead were paying tribute to a warlord named Sveneld. When Igor arrives in Drevlia he extracts the tribute “by violence” and starts returning with his followers to Kyiv.

At some point on the journey back he decides he wants even more tribute, so he tells his followers to continue on without him, he’s just going to head back to Drevlia real quick and exact some more tribute.

“Go forward with the tribute,” he tells them. “I shall turn back, and rejoin you later.”

The Drevlians hear he’s returning, and consult with their leader, Prince Mal, who says:

If a wolf come among the sheep, he will take away the whole flock one by one, unless he be killed. If we do not thus kill him now, he will destroy us all.

The Drevlians meet Igor and a few of his followers on the road and kill them all. A Byzantine source says he’s killed by bending two birch trees to the ground and tying one to each of his legs. The Drevlians then release the trees so that they straighten up and rip his body apart.

5. Olga

Igor’s wife, and by far the baddest of the Rus’ rulers. Their son Svyatoslav is only three years old when Igor is killed, so she becomes regent after Igor’s death. If you thought the previous leaders were hardcore, Olga makes them look like amateurs.

The Drevlians, after killing Igor, send a party of twenty men by boat to Kyiv to demand that Olga marry Prince Mal, the one who just murdered her husband. She receives them graciously, telling them to return to their boat and that she will call on them tomorrow. She tells them that, when called on, they should tell her people to carry them in their boat to her castle.

The next day she sends messengers to them saying, “Olga summons you to great honor.” As instructed, they tell the messengers to carry them in their boat to the castle. The Rus’ people witnessing this are disheartened, because the Drevlians just killed their leader and now are being carried honorably in a boat to take his wife. When the boat arrives at her castle, she has all of the Drevlians thrown into a trench that she had dug the night before. She bends over and inquires “whether they found this honor to their taste.” They respond that they did not. She then buries them alive.

Meanwhile, nobody else in Drevlia has heard about this, so she sends messengers there saying that the Drevlians should send their best men to Kyiv to escort her. The best Drevlian men arrive in Kyiv to receive Olga and escort her to Prince Mal. Before she meets with them, she has a large bath drawn up and instructs them to bathe. While they’re in the bath she boards up the building, sets it on fire, and burns them all to death.

She is not done with the Drevlians yet. Not even close.

The rest of Drevlians still haven’t gotten word of all this, since there haven’t been any Drevlian survivors, so Olga keeps the ruse going. She sends a message to Drevlia:

I am now coming to you, so prepare great quantities of mead in the city where you killed my husband, that I may weep over his grave and hold a funeral feast for him.

The Drevlians, unaware that Olga is on a vengeful Drevlian killing spree, gladly prepare the feast. She arrives in Drevlia and has her followers serve the Drevlians during the feast. Once the Drevlians are drunk, she orders her men to slaughter them, killing 5,000 in all.

She then returns to Kyiv and prepares her army for war against Drevlia.

In 946 she lays siege to their capital city of Iskorosten’, but they manage to hold out for a year. After a year spent subduing all of their other cities and besieging their capital, Olga finally convinces the Drevlians to sue for peace. They’re still afraid that she wants revenge (spoiler alert: she does), but she convinces them that her wrath has been quenched by all the destruction she has wrought thus far. All she wants is a small tribute: if each household in the city sends her three sparrows and three pigeons, she will return to Kyiv. This sounds like a great deal, so the Drevlians comply. But then, her final coupe de grace:

Now Olga gave to each soldier in her army a pigeon or a sparrow, and ordered them to attach by a thread to each pigeon and sparrow a piece of sulphur bound with small pieces of cloth. When night fell, Olga bade her soldiers release the pigeons and the sparrows. So the birds flew to their nests, the pigeons to the cotes, and the sparrows under the eaves. Thus the dove-cotes, the coops, the porches, and the haymows were set on fire. There was not a house that was not consumed, and it was impossible to extinguish the flames, because all the houses caught fire at once.

Sulfur is flammable, but doesn’t just spontaneously combust, so it’s possible her soldiers set the sulfur matches on fire before releasing the birds. Or maybe there’s something lost in translation. Either way, it’s a cunning trick that completely burns the Drevlians’ capital to the ground. (The Unites States experimented with doing something similar to Japan in World War II, using bats and incendiary bombs, but it was never actually used.) She captures everyone fleeing the burning city, kills some of them, enslaves some others, and extracts a heavy tribute on the rest and goes home.

Olga bucks the family tradition of attacking Constantinople. Instead, in the late 940s or 950s, Olga travels there and the Emperor Constantine VII personally baptizes her into Christianity. Constantine tries to marry her a couple of times, but she says no and returns to Kyiv. She tries unsuccessfully to convert Svyatoslav, who is now the leader of the Rus’, but she does manage to build a few churches and convince him to be more tolerant of Christians.

Later in life, Olga helps coordinate the defense of Kyiv from a Pecheneg attack while Svyatoslav is away fighting another war. One of the people trapped in the besieged city with her is her grandson, the future ruler Vladimir the Great, who would have been maybe nine or ten years old at the time.

Olga dies of illness in 969. Vladimir becomes ruler of Kyivan Rus’ in 978 and converts to Christianity in 988, the major turning point in the Christianization of the region. Because of Olga’s work in paving the way for Christianity in Kyivan Rus’, the Orthodox Church decides to overlook her homicidal tendencies and names her a saint in 1547.

The two main theories about who the Rus’ were are referred to as the “Normanist theory” and the “Anti-Normanist theory.” The Normanist theory is the one most widely accepted by historians. It says that the Rus’ came from Scandinavia. They essentially became an elite ruling class that ruled over a loose federation of Slavic, Baltic, and other tribes in the area to create Kyivan Rus’. The Anti-Normanist theory posits that Kyivan Rus’ was created by the Slavic tribes that already lived there, and that the core elements of its social and political structure were already in place before the Varangians arrived. The Normanist vs. Anti-Normanist argument seems to be heavily politically or even racially motivated, with different ruling parties over the years using one or the other as propaganda to justify whatever their particular political objectives were. The Nazis used something like the Normanist theory to show how “superior” Germanic peoples civilized the “inferior” Slavs. The Soviet Union, and later, Russia, used something like the Anti-Normanist theory to justify expansionist policies on ideological grounds.

There is a lack of reliable contemporary sources either way. This is the sort of thing that people spend their whole careers studying, so we’re not going to solve it here. I’ll settle for accepting that both theories probably have some valuable historical insights to offer. Rulers are going to use variations on each for their own purposes regardless of whatever actually happened. Knowing this can at least help to recognize it when they do.

The prior arrival of Rus’ envoys in Constantinople in 838 and Francia in 839, coupled with Nestor’s claim that they were initially kicked out of Novgorod in 859, implies that the Rus’ were present in Eastern Europe for some time prior to the existence of written records about it.

One speculative theory that might explain why the local tribes invited the Varangians back to Novgorod, if they did indeed invite them back, is that they were invited as sorts of mercenaries that would help the tribes fight against their more powerful enemies. That the Varangians could have been invited as mercenaries but ended up taking power is not far-fetched. Pretty much the same thing happened with the Normans in Sicily and southern Italy a little over a century later.

Another theory is that they arrived to trade with the East and just kind of stuck around.

Photios, Ignatios’s replacement as Patriarch, also gave two sermons about the attack, which place it as occurring in 860.

Alexander Vasiliev, The Russian Attack on Constantinople in 860, lays out numerous sources and theories for all the people and events surrounding the attack. It was written in 1946, so it’s possible new information has come to light since then, but I found it very informative. You can read a free version on the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/193332018Vasiliev1946TheRussianAttackOnConstantinopleIn860/

Apparently Oleg is a character in Season 6 of Vikings, although I have not seen it.