His Hubris Shall Be His Downfall: The Mouse-King Hath Left His Castle Totally Undefended

We shall lay it to siege!

‘Twas hubris built these walls, and ‘tis hubris which shall bring them down. The Mouse-king, in his infinite arrogance and scorn for his enemies, hath built a grandiose castle for he and his kin, and yet he hath left its walls wholly undefended!

Doth the fool think so highly of himself that he can fend off any attack without so much as a regiment of archers and men-at-arms?

Dark forces gather the land o’er, but the Mouse-king and his ilk live in a fantasy world of everlasting festivities and commoditized joy, deliberately ignorant to the coming storm. Rather than raising the drawbridge and donning their armor, they are eating sweet cotton and marching in parades. Rather than hardening defenses and sharpening their swords, they are playing frolicsome host to wide-eyed children and suckling babes.

Their hubris knoweth no bounds!

The Mouse-king, in his incalculable pomposity, was so bold as to construct his fortifications on the vast open plains in a lush growing region, leaving the castle with no natural defenses save his boundless pride.

“But theirs is a peaceful kingdom of play and magick,” one may rejoin. “They wish no ill upon any of us.”

Peaceful, you say? How dare thee speakest of peace in a kingdom which harbours foul beasts such as this:

“But the Royal Mouseketeers are amongst the most fearsome swordsmen in all the land,” one might impart. “Surely they shall defend Castle Mouse to the last.”

To the last, indeed! Their fearsome reputation is but a farce. A simple cavalry charge will cut through Mouseketeer flesh like butter.

The Mouse-king and his Mouse-court can skip and sing all they want — whilst totally ignoring the responsibilities of defending their realm from attack — but no amount of singing or overpriced ale shall keep war from their doorstep. Let this be a warning to the Mouse-king of Mousecastle: Thy Hubris Shall Be Thy Undoing!

Addendum: Castles

Note: Bret Devereaux at ACOUP wrote a great series on fortifications a few months back, one part of which covered castles. Much of that article inspired this one. I recommend reading it for a more detailed look at castles and fortifications in general.

If there’s one image that defines the Middle Ages in most people’s minds, it is the castle. Castles began to emerge in Europe in the 9th and 10th centuries, and really took off from the 11th century onwards. Military fortifications of various sorts had already existed for thousands of years, but what was unique about castles was that they were military fortifications that also served as the private residence of a lord or noble. Some ways to think about different types of castle-like structures, which Wikipedia lays out pretty well:

Castle - fortified, and the residence of a noble/lord

Palace - residence of a noble, but not fortified

Fortress - fortified, but not necessarily the residence of a noble

Fortified settlement/walled city - a fortified town or city, for the protection of all the residents in addition to the lord(s)

Hillfort - a mainly Bronze Age/Iron Age forerunner of the castle made primarily of earthworks. Largely out of use or replaced by castles by the Middle Ages

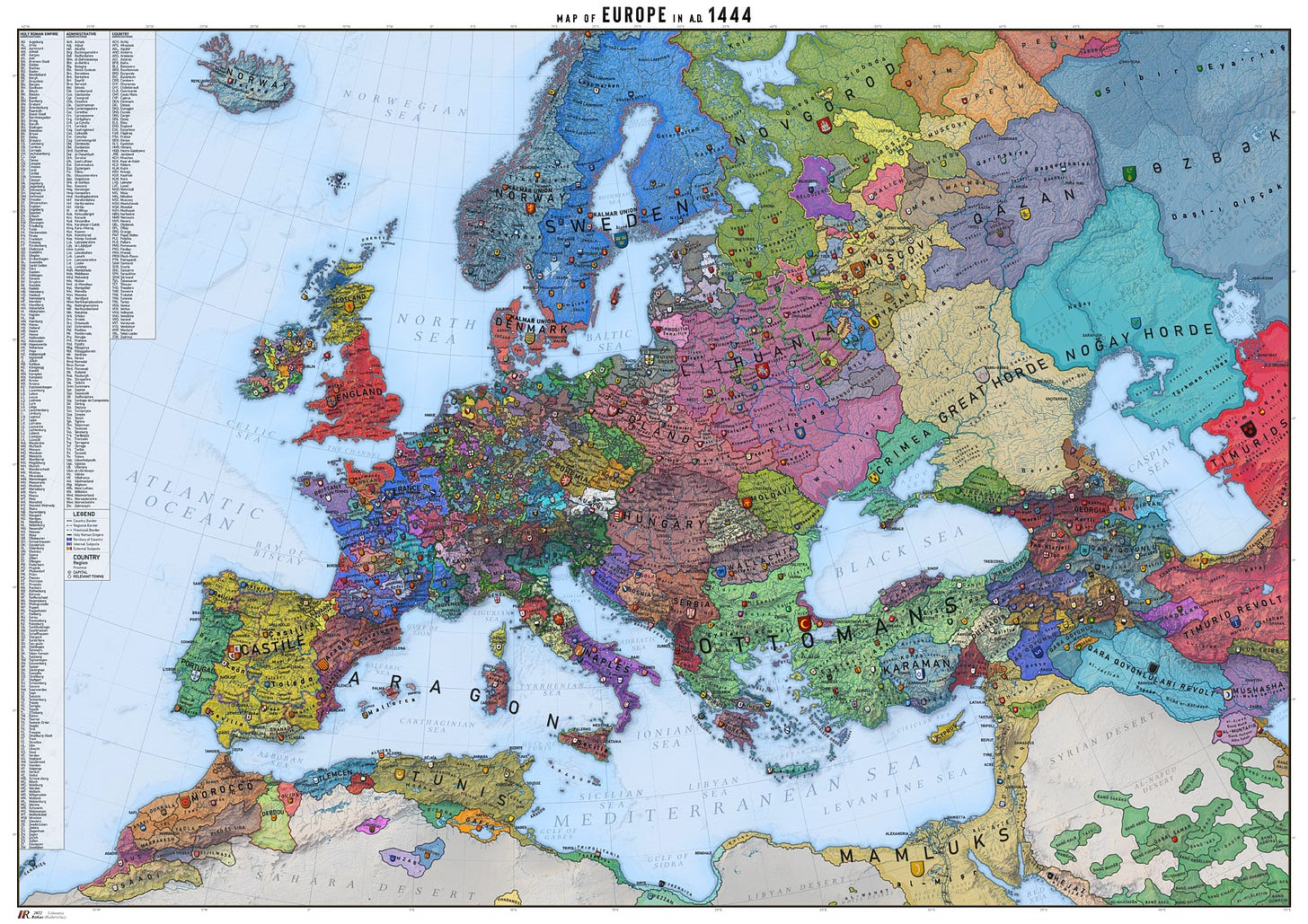

The “private residence of a lord” element of the castle is a defining feature that both shaped and was shaped by the environment of the Middle Ages. After the fall of the Roman Empire, and later the Carolingian Empire, Europe was fractured. Small-time lords could exert much more authority over local matters than they could have when big brother Rome or Aachen was watching over them. This, in turn, made large scale military action more difficult, since there was no central government or universally recognized body from which to coordinate operations. (Except the Church, which, for better or worse, was able to coordinate the Crusades. Probably for worse.) It was very hard to put a large army in the field, and even harder to feed, supply, and pay them once they were there.

Along with this fractured and decentralized power structure came raiding and pillaging. Living on the borders of the former empire could leave you exposed to raids by Vikings, Arabs, or one of the many tribes coming out of eastern Europe and the Eurasian Steppe, not to mention your fellow lord from the next fiefdom over. One way to defend against raids - as well as provide a launching point for them - was the castle.

In a fragmented geopolitical landscape, castles made sense. Their purpose wasn’t to defend against large armies. Their purpose was for the local lord to control the surrounding countryside and defend against raids and small scale invasions. The castle could serve as a base to launch raids into surrounding lands, and could also serve as a defensible place of refuge for the local people during an enemy raid. It was the home of the ruling family of the area, as well as a hardened center of commerce, which gave people a safe location to conduct economic activity while also making it easier to collect taxes from them (why send the tax collector around the fiefdom if you can get all the taxpayers to come to you? Suckers!).

To take a castle would require besieging it, and that required more troops, time, and logistics than most small-time lords or pillagers-just-passing-through could afford. So the cost of besieging a castle, and hence of conquering someone else’s territory, was greater than most were willing or able to pay. The presence of a castle in your territory could (hopefully) keep war at the level of raiding/plundering, or cause invaders to completely bypass your castle without escalating into a full scale siege or battle. This both solidified a lord’s power over his local demesne, and also led to further fragmentation on a wider scale, because if you had enough money and a handful of loyal troops, all you had to do was build a castle and pretty much nobody could mess with you.

Evolution of Castles

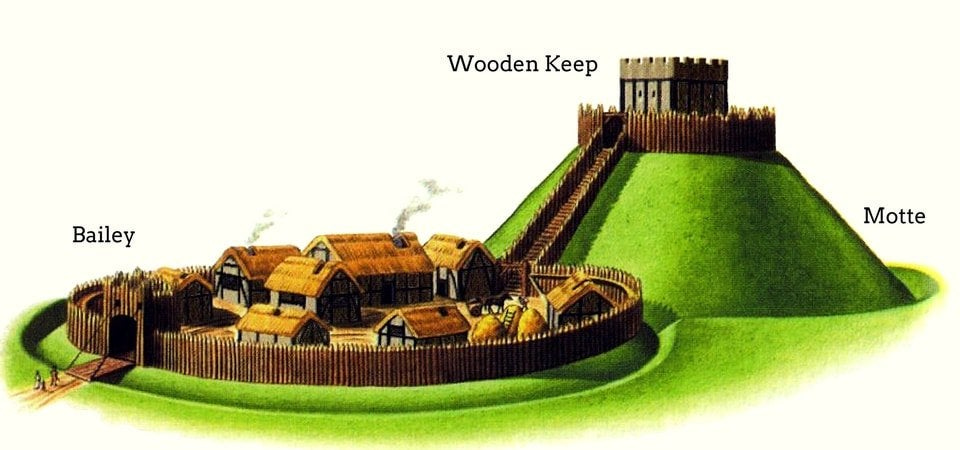

One of the earliest styles of castle was the “motte-and-bailey.” It consisted of a “motte” (or mound) of earth with a “keep” at the top where the lord lived. The “bailey” was a larger fortified enclosure built adjacent to the motte (sort of like a big courtyard) which contained other buildings such as horse stables, workshops, and housing for the non-lords. Motte-and-bailey castles seem to have been especially prominent after the Norman conquest of England in 1066. Early motte-and-bailey fortifications and keeps were built of wood, but over time wood was replaced by stone.

The structure was also commonly surrounded by a moat, a ditch dug around the outer wall, sometimes filled with water. A wooden motte-and-bailey castle, surrounded by an empty moat and sitting on top of a 10-meter high pile of dirt looks hilariously useless as a defensive structure. But remember, its purpose wasn’t to fend off a months-long siege by a disciplined imperial army. Its purpose was to keep out whoever happened to be wandering through looking to plunder. From the perspective of a raider, attacking into and across a moat then climbing a near-vertical mount of dirt while getting arrows shot at you would make you seriously reconsider attacking this place. They were relatively cheap and easy to build, and so obtained their desired result for low cost.

The next evolution of castles can be called the “stone keep.” Technically a motte-and-bailey could also have a keep made out of stone, and many motte-and-bailey keeps were later upgraded with stone. The main distinction here is that the keep was moved inside the bailey as a free standing structure and was protected by the curtain wall, whereas in the motte-and-bailey the keep was sort of separate from everything else on top of a mound.

Building off of the stone keep model, castle builders started adding concentric rings of fortified walls, so that a defender would have to break through multiple layers of fortifications to reach the keep. These appeared later in the Middle Ages and would have been massively expensive to build. So by the time they appear, the fractured, decentralized medieval world is already starting to consolidate into larger political entities. The larger of these would likely no longer be the residence of a single lord and his family, but the residence of multiple lords or the leaders of a group such as the Templars.

A fourth type of castle came into being after castles had lost all practical usefulness. That is, castles built by extremely wealthy people solely to display their wealth and power, or out of a romantic longing for the bygone days of yore. Like this one:

Effects of Castles on Warfare

So castles were both a result of and contributor to the fragmented world of post-Carolingian Europe. In terms of the effects this decentralized situation would have on the regularity and scale of war in the period, I’d imagine it would lead to near constant small scale war and minor military-like actions, but relatively few large international wars. Contrast this with, say, the 1600s until World War II — when states became bigger and more centralized and military technology became more destructive — which would see periods of relative peace punctuated by bouts of massively destructive international war.

The chart below seems to confirm this to some extent, although I would have expected slightly fewer small wars in the 1800s and early 1900s, and a few more in the 1400s and 1500s. My guess is some of the discrepancy is simply because we have better data for the past 200 years than we do for the 1400s, especially for places outside of Europe, the Middle East, and China.

Starting with the Thirty Years’ War (1618-48), the highs and lows of deaths in conflict are much more extreme and seem to recur almost cyclically, whereas pre-1600 it’s more or less a flat line of consistent small-ish wars.1

The Wikipedia page on wars by death toll lists 13 wars with 25,000 or more deaths between the years 500-1500 AD, only nine of which involved Europe. Compare this with the years 500 AD and before, which had 24 such wars; and 1500 to the present, which has had 147 wars with over 25,000 deaths.2 For the big medieval “wars”, many of them weren’t necessarily distinct wars, but were series of events that unfolded over the course of centuries (e.g., Reconquista 711-1492; Arab-Byzantine Wars, 629-1050; Crusades, 1095-1291; Mongol invasions, 1206-1368). Data from 1500 and before is probably not that great, but the periods pre-500 and post-1500, which tended to have larger centralized governments than in the Middle Ages (and no castles), certainly saw more large scale wars.

Again, castles were just part of the equation. Lots of small lords with no central authority led the small lords to build castles to protect themselves. Castles, in turn, allowed the small lords to maintain semi-autonomous local power, thus further contributing to fragmentation.

Of course, this trend eventually reversed. One reason was gunpowder. Specifically, cannons. The Ottoman army used cannons to break through the famous walls of Constantinople and take the city in 1453. Gunpowder and cannons became more widely adopted in Europe throughout the 15th and 16th centuries, which diminished the defensive utility of castles. Cannons increased the chances that you could besiege a castle and win, thus making attacking them more alluring and perhaps breaking the trend of “small scale raiding only.” This had a mutually reinforcing relationship with Europe’s trend towards consolidation into larger nation-states. Bigger, richer states had greater resources to conduct extended sieges. Combine this with cannons, and a castle was no longer of much use to a small time defender. Better to throw in your lot with the guy with the big guns.

The size of castles and the ability of armies to conduct sieges would have differed depending on when and where you were. In the Byzantine or Arab world, they would have had more resources to build larger fortifications as well as to conduct large scale sieges.

But in a fragmented world of semi-independent small lords who really only cared about managing their own demesne, castles were the way to go.

I would have liked to see this chart extended back another 800 or 900 years to capture trends during the “Viking era,” the Arab and Mongol conquests, the Crusades, and more of the Middle Ages in general, but I imagine the data is very incomplete.

Of course, record keeping for the past 500 hundred years is much better than it was in the previous few thousand, and it’s also Wikipedia, so it’s reasonable to be skeptical of these numbers. But I think it still captures the general sense about the frequency of large wars in different time periods.